This article dives deep into that fascinating chapter of history, uncovering how Finland’s assistance (paired with Estonians’ own determination) set the stage for Estonia to become the thriving, developed nation it is today.

The Road to Re-Independence: Estonia’s Singing Revolution

By the late 1980s, Estonia – a small Baltic nation of about 1.5 million people – was yearning for freedom from Soviet occupation. Reformist policies in Moscow had opened space for national movements, and Estonians seized the moment through song and protest. In September 1988, an estimated 300,000 people (nearly one-fifth of the country’s population) gathered at Tallinn’s Song Festival Grounds to sing patriotic hymns in a demonstration of unity and defiance. These massive song festivals and rallies, later dubbed the Singing Revolution, galvanized public support for independence in a remarkably peaceful way. Estonians en masse defied Soviet authorities – for example, by publicly singing nationalist songs that had been long suppressed – yet avoided violent confrontation. While pro-independence protesters in Lithuania and Latvia faced deadly crackdowns (14 killed in Vilnius and 6 in Riga in early 1991), miraculously not a single life was lost in Estonia’s independence process.

Behind this peaceful revolution were countless acts of courage and organization by Estonians. Activists like Heinz Valk (who coined the term “Singing Revolution”) and emerging leaders like Lennart Meri, Edgar Savisaar, and others marshaled popular momentum. By 1988–1990, Estonia had formed mass political movements (such as the Popular Front) and even obtained a measure of autonomy from the collapsing USSR. In August 1989, Estonians joined Latvians and Lithuanians in the famous Baltic Way – a human chain of some 2 million people linking hands across 600 km to demand freedom. All these grassroots efforts built a sense of inevitable independence. But as Estonia pressed forward, it did not do so entirely alone. Across the Gulf of Finland, their kindred nation quietly stepped in to help prepare the ground for Estonia’s rebirth.

Finland’s Delicate Balancing Act

Finland shares close cultural and linguistic ties with Estonia – the two Finno-Ugric peoples often affectionately call each other “sister nations.” Yet in the 1980s, Finland’s ability to help its occupied sibling was constrained by realpolitik. Finland had a policy of strict neutrality (some say “Finlandization”) in order to coexist with its giant neighbor, the Soviet Union. Finnish President Mauno Koivisto epitomized this careful line. Publicly, Koivisto maintained that Finland could not interfere in Soviet internal affairs and acknowledged the de facto status quo of Estonia being part of the USSR. In January 1991 – when Soviet troops attacked pro-independence demonstrators in Vilnius and Riga – Koivisto’s cautious statements (appearing to blame “radicals” and urging solutions within the Soviet constitution) drew anger from many Estonians and even Finns. To outsiders, it seemed Finland was turning its back on Estonian freedom.

Privately, however, the Finnish leadership had made a very different decision. As early as 1988, President Koivisto and his inner circle resolved to assist Estonia’s independence aspirations as much as possible – just never overtly. Good relations with Moscow had to be maintained, so any aid must be concealed. The guiding principle, formulated by Finnish officials like diplomat Jaakko Blomberg, was: support the Baltics’ independence, keep Moscow placated, and never let those two goals openly conflict. Koivisto, a shrewd strategist, found the perfect cover story in one word: culture. As he famously quipped to his Minister of Education and Culture, “Well, you can practice a lot of things in the name of culture.”

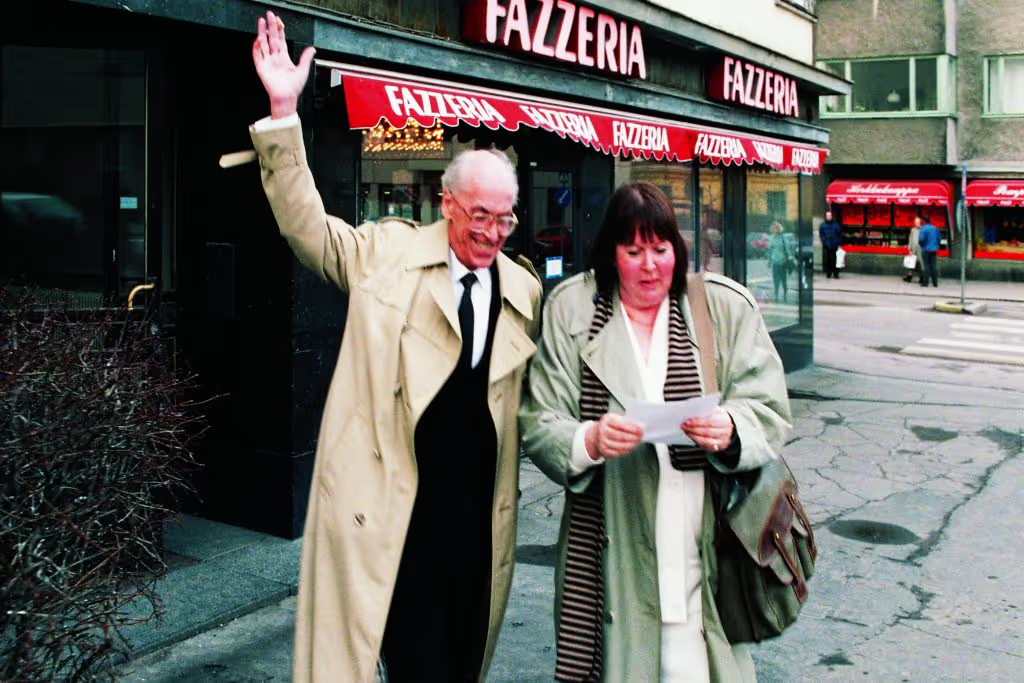

Finland’s President Mauno Koivisto (in office 1982–1994) publicly toed a neutral line toward Estonia, but behind the scenes he authorized covert aid “in the name of culture”.

“In the Name of Culture”: The Covert Aid Operation

Beginning around 1988, Finnish authorities quietly funneled resources to support Estonia’s quest for statehood – all under innocuous labels like cultural exchange, education, or trade cooperation. Historian Heikki Rausmaa, who studied declassified archives, found that Finland provided over 100 million Finnish Marks (equivalent to ~€16–24 million) in aid to Estonia by 1991. This was a huge sum at the time for a country of Estonia’s size. Crucially, it wasn’t a public grant or loan program; the funds traveled a circuitous route: from the Finnish state budget to various ministries, then to front organizations, companies, and NGOs which in turn delivered assistance across the Gulf. By design, it would not be obvious that “Finland” was bankrolling the Estonians – it would look like private or grassroots cooperation.

One key conduit was the Tuglas Society, a Finnish-Estonian cultural friendship association. The Finnish Ministry of Education (led by Minister Anna-Liisa Kasurinen) was given primary responsibility for the Estonia program. They bolstered the Tuglas Society and a Finnish-Estonian Cultural Association with funding, even providing office space next to the Ministry in Helsinki. These offices effectively became the unofficial “Estonian government in exile.” In fact, future Estonian president Lennart Meri worked out of the Tuglas Society’s Helsinki office, coordinating plans for independence. Koivisto had told Meri that whatever he needed for the cause, Finland would try to provide – the only condition was absolute secrecy about Finland’s role. Meri kept that promise to his grave, never publicly crediting Finland for its help, as Koivisto had requested.

Under the umbrella of “cultural cooperation,” a remarkable range of support flowed: Financial aid, expert advice, training, material goods – even moral support. A few examples illustrate how thorough this covert operation was:

- Financial Support for Institutions: Finnish funds were used to (re)build Estonia’s government infrastructure in advance. Everything from drafting a new banking system and currency to setting up ministries and local administrations was assisted by Finnish experts behind the scenes. By one estimate, when Estonia finally declared independence in August 1991, roughly 400 million Finnish Marks were already circulating in Estonia’s economy to keep it stable. (Tellingly, when Estonia launched its own currency, the kroon, in 1992, the foreign reserves backing it were about the same amount.) In short, Estonia did not start from zero – it had a financial cushion and proto-institutions thanks to covert aid. As Rausmaa notes, “In reality, Estonia did not start with nothing in 1991… it already had crude but functioning institutions [and] financial aid” in place.

- Education and Training: Anticipating that a free Estonia would need competent leaders and officials, Finland covertly expanded educational exchanges for Estonians. Dozens of young Estonians were brought to Finnish universities and training programs in 1988–1991, grooming a generation of public servants, economists, and experts who would later run the country. Finnish advisers also traveled to Estonia (unofficially) to consult on setting up a market economy and democratic governance. After independence, this collaboration became more open: for instance, Finland helped establish Estonia’s Police Academy in 1990 and hosted training for new police recruits. The Finnish Defence Forces likewise began training Estonia’s resurrected military – by June 1992, the first cohorts of Estonian officers were studying in Finland to professionalize the Estonian Defence Forces.

- Material Aid: Beyond money, Finland provided a great deal of equipment and supplies to Estonia’s emerging institutions. It donated office equipment, computers, telecommunications gear, vehicles, and other essentials to help set up everything from government offices to local police stations. Finnish farmers famously organized drives to send over tractors and farm machinery to their Estonian counterparts, helping to jump-start agricultural productivity on newly privatized Estonian farms. Finnish schools “adopted” Estonian sister schools, raising funds to send books, clothing, and school supplies across the gulf. Much of this was done by civil society groups with a wink of approval from the state, so it appeared as humanitarian or cultural generosity rather than official aid.

- Covert Ops and Solidarity: Some support efforts were more cloak-and-dagger. Finnish activists printed postcards bearing photos and names of imprisoned Estonian dissidents, then mailed them in bulk to Soviet authorities – a subtle form of pressure, as the cards would be handled by many in the postal system before reaching the Kremlin. There were also instances of Finnish volunteers smuggling banned literature, fax machines, and even photocopiers into Estonia (tools that proved useful for the burgeoning independent press and civic movements). While these grassroots acts were not directed by the Finnish government, they thrived in an atmosphere that Koivisto’s policy enabled. Indeed, Rausmaa notes that Finnish “obfuscation tactics” fooled even many Finns – the Finnish public largely believed their government was doing little, so ordinary Finns took it upon themselves to help their “little brother” nation. The result was a two-level effort: a covert state-sanctioned operation and an outpouring of popular support.

Rock, Song, and Airwaves: Cultural Support and Psyche Boost

Finland’s contribution wasn’t only in spreadsheets and secret meetings – it was also in the hearts and minds. Culturally, Finns and Estonians had maintained contact even during the Cold War, and this ramped up as Estonia neared independence. Music and media played a special role. In August 1988, a daring event called “Glasnost Rock” (or Rock Summer ’88) was organized in Tallinn with help from a Finnish DJ and entrepreneurs. Ostensibly just a music festival – the first of its kind in Soviet Estonia – it featured popular Finnish rock bands (such as Eppu Normaali, Juice Leskinen, and the parody rockers Leningrad Cowboys) alongside Estonian and even Western performers. The festival drew over 150,000 ecstatic spectators and took on an electrifying political tone. During one set, Finnish singer Sakari Kuosmanen couldn’t resist shouting “Eesti vabaks!” (“Free Estonia!”) from the stage – the vast crowd roared and waved blue-black-and-white Estonian flags in response. Soviet militia on site chose not to intervene; as one performer noted, “it is impossible to arrest 200,000 people” in unison. The rock concert that never ended, as it’s been called, became part of Estonia’s independence saga – and it was Finnish musicians who literally helped Estonia sing itself free.

Another quirky Finnish “aid” came via television. For years, many northern Estonians could pick up Finnish TV broadcasts with improvised antennas – a rare window to the free world. Finnish channels carried Western news, entertainment (like the soap opera Dallas), and the kind of uncensored truth absent in Soviet media. Soviet authorities hated this and reportedly pressured Finland to move a certain Tallinn-adjacent transmitter. The Finns politely claimed “technical impossibility” and left things as they were. The result: by 1990, an entire generation of Estonians had grown up with Finnish television shaping their mindset, subtly undermining Soviet propaganda. A 2009 documentary titled “Disco and Atomic War” even explores how pivotal this TV was in Estonia’s revolution. In a sense, Finland’s free press and pop culture were unwitting liberators too – spreading ideas and hope across the gulf.

Meanwhile, countless people-to-people exchanges took place. Choirs from Finland toured Estonia and vice versa; Finnish cities sent invited Estonian delegations under city “twinning” programs; even the famed Finnish satirical band Leningrad Cowboys staged concerts poking fun at Soviet symbols (famously performing “Sweet Home Alabama” with the Red Army Choir in a tongue-in-cheek production). These cultural interactions kept Estonians’ spirits high and reminded them they hadn’t been forgotten by the West. As one slogan put it: “Don’t give us fish, give us fishing equipment.” Finland largely followed that wisdom – empowering Estonians to help themselves, rather than imposing solutions.

A Peaceful Victory and Prepared Future

Thanks to the Estonians’ own resolve – and with Finland’s discreet help – Estonia was ready when the Soviet regime finally buckled. On August 20, 1991, as hardliners’ coup in Moscow faltered, Estonia’s parliament courageously declared full restoration of independence. The very next day, Iceland became the first country to diplomatically recognize Estonia’s independence (while President Koivisto was still cautiously saying it “permits… conditions to gain independence in the longer term” on TV). But Koivisto’s quiet groundwork paid off: within days, several major Western nations recognized Estonia, thanks in part to introductions and lobbying done earlier by Lennart Meri and Finnish diplomats. (It was said that in the days following the declaration, Meri was driven around Helsinki in a limousine bearing the Estonian flag, stopping at various embassies to secure signatures on Estonia’s recognition documents – a stark contrast to 1918, when Estonia had to beg for Moscow’s acceptance.) Finland itself formally re-recognized Estonia on August 25, 1991 – noting pointedly that it was merely restoring the diplomatic ties first established in 1920. Koivisto had timed this so that it came right after Russia’s President Yeltsin endorsed Baltic independence, thus avoiding any direct clash with Soviet authority. By September 6, the Soviet Union’s state council also acknowledged Estonia’s independence, without a drop of blood spilled in Estonia.

If avoiding bloodshed was Koivisto’s paramount goal, he succeeded. “Koivisto was very careful… he did not want any bloodshed; it was to happen peacefully,” noted one analysis of Finland’s role. He had privately urged Estonian leaders to avoid any provocation or unilateral clashes with Soviet forces – advice they heeded, even during tense moments with Soviet troops in Tallinn. The result was a uniquely peaceful liberation. Estonia emerged free, with its people jubilant – and importantly, with a functioning proto-state ready to roll out. Lennart Meri and his team, having sketched out plans in Helsinki, moved swiftly to establish a foreign ministry, a central bank, and other institutions in Tallinn in the fall of 1991. With Finnish (and broader Nordic) advisors at their side, they instituted a new currency (the kroon) by mid-1992, pegged to the stable German mark. They implemented democratic elections, legal reforms, and economic liberalization with breathtaking speed. In many ways, they followed the Nordic model – for example, trimming state control and embracing open markets, similar to Finland’s approach, which greatly accelerated post-Soviet recovery.

The impact of this head start is evident in Estonia’s later success. Over the next decades, Estonia transformed into one of Europe’s most dynamic and digitally advanced economies. Foreign investment poured in, especially from Finland and Sweden, which saw Estonia as a natural partner. In fact, Finland quickly became Estonia’s #1 trading partner and the second-largest source of direct investments throughout the 1990s and beyond. Joint ventures in banking, telecommunications, and manufacturing flourished across the Gulf of Finland, further knitting the two economies together. Culturally and socially, the ties also grew – tens of thousands of Estonians moved to Finland for work, while Finnish tourists and retirees flocked to Estonia. By many measures, Estonia steadily closed the gap with its Nordic neighbors. In an illustrative comparison of well-being, in 1992 Estonia’s economic output per person was only about 22% of Finland’s level, but by 2018 it had surged to 83% – an astonishing convergence. Today, Estonia is a proud member of the EU and NATO, often lauded as a Baltic Nordic success story.

Brothers in Freedom

Estonia’s re-independence story is, first and foremost, a tribute to the indomitable spirit of the Estonian people. They sang their way to freedom and then worked tirelessly to build a new country from the ashes of Soviet rule. At the same time, the story would be incomplete without recognizing the secret role played by Finland – the supportive “big brother” who, while walking on eggshells diplomatically, never lost sight of a moral duty to help. Finland’s financial and logistical support between 1988 and 1991 gave Estonia a critical boost, helping ensure that independence, when it came, could immediately be sustained. It was an act of solidarity grounded not in headlines or grand speeches, but in quiet deeds: a budget allocation hidden in a “cultural” grant, a shipment of computers labeled as “education aid,” a training seminar held in a remote Finnish town, a rock band yelling “Free Estonia” under the nose of Soviet officials. These efforts exemplify how a country can extend influence and support through soft power and clever subterfuge.

In one of his few reflections on that period, President Koivisto humbly said in late 1991, “It is not general knowledge in Estonia – and it never will be – all the things that Finland has done for Estonia.” Indeed, for many years the full extent of the “Estonia operation” remained hidden, as agreed. But today, with archives opened and research done, we can acknowledge this extraordinary chapter of Nordic brotherhood. The outcome was a win-win: Estonia regained nationhood peacefully, and Finland gained a thriving, democratic neighbor. The two countries are closer than ever – bound by history, culture, and mutual respect.

As Estonia’s beloved Lennart Meri once said, “Don’t give us the fish. Give us the fishing equipment instead.” Finland did exactly that. Estonia took the gear, cast its line, and today reaps the rich catch of freedom and prosperity – a testament to both self-determination and supportive friendship in a pivotal moment of history.

.png)

.png)

.png)