Järvi and the orchestra were joined by star violin soloists Midori and Hans Christian Aavik, composer-pianist Nico Muhly, and the Grammy-winning voices of the Estonian Philharmonic Chamber Choir, all contributing to an unforgettable evening. This event, part of Carnegie Hall’s season-long celebration of Arvo Pärt at 90, was more than just a concert – it was a cultural milestone that lived up to its great expectations.

Arvo Pärt at 90: A Celebratory Season and Cultural Milestone

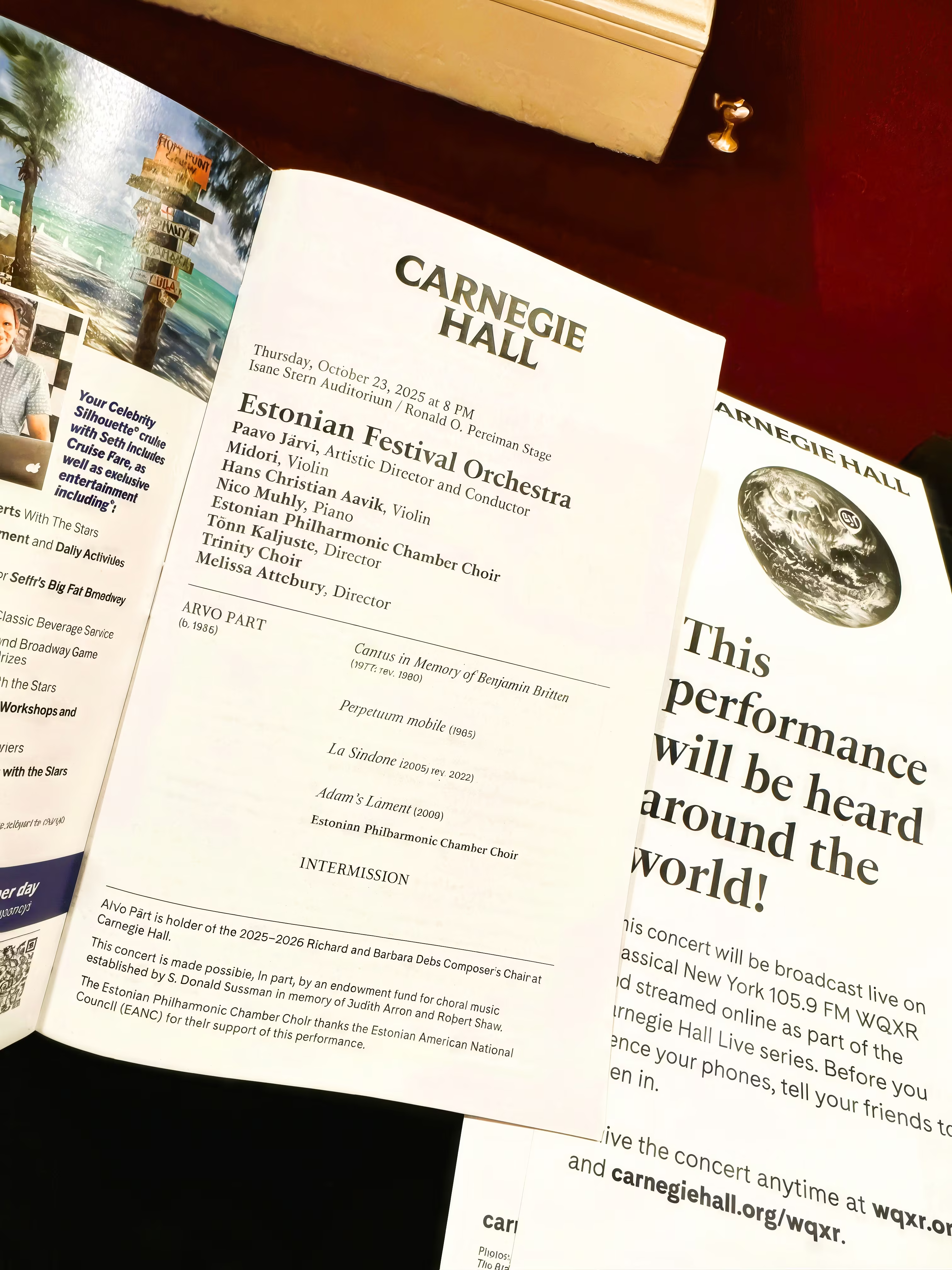

This concert was the opening salvo of a broader Carnegie Hall retrospective honoring Arvo Pärt, who is among the world’s most performed living composers. Pärt turned 90 on September 11, 2025, and Carnegie Hall named him to its Richard and Barbara Debs Composer’s Chair for the season. The October 23 performance launched a planned series of seven concerts devoted to Pärt’s music over the 2025–26 season. For New York audiences, it was a rare chance to immerse in the “mystical, singular, incomparable… and yet universal” sound-world of Pärt. “[His music] fulfills a deep human need that has nothing to do with fashion,” as composer Steve Reich once observed – an insight borne out by the profound connection felt in the hall that night.

Beyond its musical significance, the event carried weight as a point of national pride for Estonia. The concert was attended by a contingent of Estonian dignitaries and cultural leaders, underscoring its importance. In fact, Estonia’s President Alar Karis and Culture Minister Heidy Purga traveled to New York that week alongside a creative industries delegation, with cultural events and even a gala dinner organized around the Carnegie concerts. “This is a dream come true for Estonian cultural diplomacy. It is hard to imagine a greater honour for Estonian culture than to present the creative genius of Arvo Pärt in New York, at Carnegie Hall,” said Estonian Ambassador Kristjan Prikk. Indeed, seeing Pärt’s music showcased on one of the world’s most prestigious stages – performed largely by Estonian artists – was a triumph of national culture on the world stage. For Paavo Järvi, who has long championed Estonian composers, the occasion was deeply meaningful. “Our country may be small, but Arvo Pärt’s iconic music is loved worldwide,” Järvi has noted – a sentiment clearly validated by the enthusiastic international audience.

A Wide-Ranging Program Spanning Pärt’s Career

Järvi and the Estonian Festival Orchestra crafted a wide-ranging program that essentially told the story of Arvo Pärt’s artistic journey. It featured significant early works, landmark pieces from the composer’s game-changing tintinnabuli style, as well as powerful 21st-century selections. Together, it was “a stunning survey of Pärt’s singular musical world, performed by many of the artists who know it best.”

The evening’s repertoire spanned nearly six decades of Pärt’s output. Among the works performed were:

- “Perpetuum Mobile” (1963) – an early experimental piece from Pärt’s avant-garde period. This short orchestral work, written in a modernist 12-tone idiom, hurtles forward with relentless energy. (Notably, Perpetuum Mobile has a special historic link to Carnegie Hall: it was the first piece by Pärt ever performed in the United States, premiered at Carnegie in 1967 by Lukas Foss and the Buffalo Philharmonic.) In Järvi’s hands, this youthful work came across as a kinetic burst of sound – “pulsating urgently like a countdown to apocalypse,” as one reviewer described, drawing a direct line to the intensity that Pärt’s music can summon even in its later simplicity.

- “Credo” (1968) – a seminal early piece for piano, orchestra, and chorus that openly quotes J.S. Bach. Credo was Pärt’s last major work before a creative crisis and spiritual turn; its bold use of a Latin sacred text and collision of tonality with atonality infamously led Soviet authorities to ban the piece in 1968. Neeme Järvi (Paavo’s father) conducted the Credo premiere in Tallinn, an event that marked a turning point in the composer’s life. Hearing Credo at Carnegie Hall felt momentous – its Mahlerian battle between light and dark (as evoked by the Bach prelude vs. dissonant chaos) came through powerfully. The Estonian Philharmonic Chamber Choir, seasoned interpreters of Pärt, sang with fervor, making the work’s message of faith and artistic freedom ring out vividly.

- “Fratres” (1977) – one of Pärt’s best-known works, heard here in an arrangement for large orchestra. Fratres (Latin for “Brothers”) is an hypnotic, open-form piece that Pärt has arranged for various instruments over the years. Its interlocking cycles of chords and drone create a ritualistic atmosphere. In the full-orchestra version, the two interwoven melodic lines characteristic of Pärt’s tintinnabuli style took on rich hues. The performance highlighted how this seemingly simple formula can yield profoundly different emotional colors – from austere agony in some passages to a sense of quiet hope in others (as would later be reflected in Swansong). The tintinnabuli approach – the bell-like harmony style Pärt developed in the 1970s – was on full display, demonstrating why it was “game-changing” in the world of contemporary classical music.

- “Tabula Rasa” (1977) – the iconic double violin concerto that stands as one of Pärt’s masterpieces. Remarkably, this was the first-ever performance of Tabula Rasa at Carnegie Hall, making it a highlight of the night. Composed in the year of Pärt’s artistic rebirth, Tabula Rasa epitomizes the purity and spiritual depth of the tintinnabuli style. It unfolds in two movements – Ludus (Game) and Silentium – that move from vigorous, swirling interplay into an otherworldly quiet. On this occasion, violin legend Midori and rising Estonian violinist Hans Christian Aavik were the soloists, with Nico Muhly at the prepared piano. They delivered a performance of extraordinary concentration. Midori’s playing was a study in poise and purity – she produced a “pure, singing tone” with remarkable bow control, even in the most hushed, glassy phrases. Aavik, for whom this concert was an American debut as well, proved to be a revelation. He attacked the first movement with sheer youthful energy and then achieved an “entrancing calm” in the tranquil second movement – never forcing, always letting the music breathe. The chemistry between the two violinists – one an established master, the other a youthful firebrand – gave Tabula Rasa an electric contrast. When the final notes of Silentium faded into silence, there was a palpable sense that time had stood still. (It is little wonder that the Carnegie audience erupted with applause – many leapt to their feet even before the program was officially over.)

- “Cantus in Memoriam Benjamin Britten” (1977) – another of Pärt’s most famous works, this elegiac canon for strings and bell has an aching beauty that unfolds in a slow, inexorable wave. Placed in the program, the Cantus served as a meditative moment of remembrance and introspection amid the evening’s extremes. Under Järvi’s direction, the orchestra’s focus and restraint were on full display here. The players sustained soft dynamics so well that the sound seemed to emerge organically out of the hall’s silence, as if “softly from the walls rather than from the instruments onstage,” to quote the vivid observation of one critic. The music built gradually, “almost through accumulation alone,” toward its emotional climax – a towering A minor chord pealing like a bell. When the final resonant toll of the tubular bell hung in the air, Järvi allowed the orchestra to linger in the “sea of sound” until it gently subsided, honoring the work’s poignancy. The effect was spellbinding, holding the audience in rapt stillness.

- “Adam’s Lament” (2009) – one of Pärt’s later choral compositions, written for chorus and string orchestra. Setting a text by Saint Silouan of Athos (in Church Slavonic and Estonian), Adam’s Lament is steeped in spiritual sorrow and repentance. For this piece, Tõnu Kaljuste (the renowned Estonian choral conductor, present as part of the delegation) joined Paavo Järvi to prepare the choir. The Estonian Philharmonic Chamber Choir brought a pure, early-music quality to their tone, illuminating the work’s ancient-Christian atmosphere. They also exposed the natural dissonances within Pärt’s tintinnabuli writing, creating exquisite tensions and releases. The orchestra supported with dark-hued string sonorities, making Adam’s Lament a deeply moving experience – a communion of voices and strings that seemed to echo in the vaulted space of Carnegie Hall.

- “Swansong” (2013) – a brief orchestral piece from Pärt’s more recent output, relatively seldom performed. In contrast to the intense lament before it, Swansong offered a morsel of consolation (as its title suggests). Over the piece’s short span, listeners could sense a flicker of light – a tender melody emerging, hinting at salvation and closure. Järvi and the EFO rendered Swansong with delicate sensitivity, making it a quiet gem tucked among the larger works.

- “La Sindone” (2005) – another 21st-century work by Pärt, inspired by the Shroud of Turin. La Sindone is built on the tintinnabuli foundation but incorporates tone rows and modernist techniques, showing that Pärt’s later style still converses with his early avant-garde approach. The opening measures of La Sindone carry an almost frightening intensity – a dense cluster of sound that startled the Carnegie audience. This “alarming spirit” at the outset created a bridge back to the edgy atmosphere of Perpetuum Mobile, demonstrating a through-line from Pärt’s 12-tone past to his sacred minimalist present. As the work progressed, the orchestra navigated its complex emotional terrain – from turbulence to reverence – highlighting the vast range of musical thought that Pärt’s simple tintinnabuli rules can encompass over time.

Taken as a whole, the program was exceptionally well-curated. It alternated between meditative stillness and explosive intensity, mirroring the composer’s own evolution. The inclusion of historically significant works (Perpetuum Mobile, Credo) alongside universally acclaimed masterpieces (Cantus, Tabula Rasa) and newer offerings (Swansong, La Sindone) made for an “expansive survey” of Pärt’s oeuvre. It was the kind of deep dive that both educated and enthralled the audience – offering newcomers a broad introduction to Pärt, and aficionados some rare treats and context. As the 21C Media press noted, this concert (and the short tour preceding it) truly encapsulated Pärt’s entire career, from early experimentations to late-period reflections. Such a repertoire is demanding to pull off in one evening, but Paavo Järvi and his forces met the challenge with superb artistry.

Masterful Performances and Profound Musical Moments

Throughout the night, Paavo Järvi’s leadership was both confident and self-effacing – very much in the spirit of Pärt’s music, which often demands humble servitude to the score. Järvi is intimately familiar with Pärt’s works (the Järvi family’s connection to Pärt was even highlighted by Pärt being a close family friend of the Järvis). That deep understanding translated into performances of remarkable clarity and conviction. Under Järvi’s baton, the Estonian Festival Orchestra demonstrated why they have quickly become a world-class ensemble since their founding in 2011. The orchestra – which unites top Estonian talent with leading musicians from around the globe – played with utter unity of purpose and a notably homogeneous sound. In Pärt’s transparent textures, every player must be in sync, and here the balance between strings, wind, and percussion (including the all-important bell in Cantus) was immaculate.

A striking feature of the concert was the extreme dynamic range the musicians achieved. At times, the orchestra played so softly that one could literally hear a pin drop – or, in this case, the faint rustle of a program or the distant rumble of the subway underneath Carnegie Hall. Those moments of near-silence heightened the music’s spiritual dimension; they drew the listeners in, inviting active concentration. Yet when climaxes arrived (for example, the thunderous chord in Credo or the fortissimo outburst in La Sindone), the ensemble delivered full, blazing power – all the more impactful after so much restraint. Järvi has a keen sense for pacing Pärt’s gradual builds. He “trusted the score,” allowing the cumulative power of repeating patterns to organically reach their catharsis (particularly evident in Cantus and the first movement of Tabula Rasa). The result was an emotional payoff that felt earned rather than forced. It takes intense focus to perform Pärt’s deceptively simple pieces – every note and every silence counts – and the EFO players were fully committed to that focus, individually and as an ensemble.

Special mention must be made of the solo contributions that night. Violinist Hans Christian Aavik, though only in his early 20s, made an indelible impression. Aavik is the 2022 winner of the Carl Nielsen International Violin Competition, and this Carnegie Hall appearance was billed as his U.S. debut – truly a baptism by fire. He rose to the occasion brilliantly. Whether digging into Pärt’s furious figuration or sustaining a feather-light harmonic, Aavik played with a maturity beyond his years. His compatriots back home will surely bask in pride at how “naturally” he channeled Pärt’s idiom – as if born to it. On the other side of the stage was Midori, an internationally renowned violinist making a special guest appearance. Midori’s presence added star power, but more importantly, her refined musicianship added a layer of polish to everything she touched. In the intricate dialogues of Tabula Rasa, she and Aavik seemed to communicate telepathically through phrases – trading echoes, matching timbres, and together sustaining the long lines with breathtaking control. Pianist Nico Muhly, himself a prominent contemporary composer, took on the unusual role of second pianist in Tabula Rasa (playing the preparatory chords that punctuate the piece) and also contributed on keyboard in other pieces. His participation symbolized a passing of the torch: Muhly, an American, has cited Pärt as an influence on his own work, and here he was literally supporting Pärt’s music alongside the Estonians. It was a beautiful example of musical camaraderie across generations and cultures.

The Estonian Philharmonic Chamber Choir (EPCC), for their part, showed why they are considered Pärt specialists. Whenever the choir entered – be it the raw, D-minor chord that opens Credo, the somber chants of Adam’s Lament, or the luminous hummed motif of the encore – they commanded attention. Their sound can shift from full-throated and earth-shaking to eerily transparent. In Credo, the EPCC conveyed the piece’s dramatic contrasts, at first intoning Bach’s Prelude in C major (from The Well-Tempered Clavier) with angelic clarity, then later unleashing bursts of chaos with appropriate ferocity. In Adam’s Lament, they rendered the Old Church Slavonic text with an authentic Orthodox feel, dark and sonorous, making the pain of Adam (symbolizing humanity) palpable. Such versatility and devotion to Pärt’s music has earned the EPCC a reputation as perhaps the finest choir for this repertoire, and their contributions on this night were essential to its success.

A Prolonged Ovation and an Encore “For Everyone”

As the final chords of Credo – the last programmed piece – faded, the audience in Stern Auditorium erupted into a standing ovation. New York concertgoers can be discerning, even jaded, but here they were unequivocally won over. Many in attendance had likely never heard the Estonian Festival Orchestra live before, and the ensemble’s debut made a powerful impression. In a touching moment, Paavo Järvi addressed the crowd from the stage. With a beaming smile, he noted that in New York, “people usually stand up at concerts only to leave” – but that night, everyone was standing to applaud. It was his lighthearted way of acknowledging how special the moment was – a rare and heartfelt exchange between a New York audience and an Estonian orchestra. The conductor’s words rang true: the ovation felt not routine but deeply genuine, a recognition that something extraordinary had just occurred.

After multiple curtain calls, Järvi and the performers offered a brief encore that perfectly capped the evening’s atmosphere. Fittingly, they chose “Estonian Lullaby,” a tender choral miniature based on a folk tune from northeast Estonia. This unaccompanied lullaby, arranged by Pärt in 2002, is disarmingly simple and sweet. The EPCC sang it with delicate nuance, as the orchestra musicians stood at ease behind them. It felt as if, after the grand statements of the main program, the artists were now sharing a quiet moment from home with the audience. The lullaby’s gentle melody and soft Estonian text created an intimate hush over the hall – a final musical benediction. Though rooted in a specific Estonian folk tradition, in that moment the song transcended its origins. It was offered as a universal gift of peace and beauty, one that any listener could appreciate regardless of background. As the New York Times aptly noted in its review, Pärt’s music – even an Estonian cradle song – “is really for everyone.”

When the last notes of “Estonian Lullaby” faded, the hall was silent for a brief moment, and then yet another wave of applause and cheers erupted. The entire audience had been held rapt, and they responded with unbridled admiration. Seasoned concertgoers remarked on the electric atmosphere – rarely does a contemporary music program (let alone one by a single composer) elicit such enthusiasm. It was a testament not only to Arvo Pärt’s unique musical voice, which can touch the soul in profound ways, but also to the passionate, world-class execution by Järvi, the EFO, and their collaborators.

Reflections on a Night to Remember

In sum, the Estonian Festival Orchestra’s Carnegie Hall concert will be remembered as a high point of the 2025 musical season – and a watershed moment for Estonian music abroad. It succeeded on multiple levels: as a showcase of Pärt’s legacy, as a demonstration of superb music-making, and as a moment of cultural significance beyond the notes. The programming was both insightful and bold, offering a panoramic view of Arvo Pärt’s artistic evolution. The performances were technically polished and emotionally resonant, doing justice to the “simplicity and power” of Pärt’s tintinnabuli language. And the occasion itself carried the aura of history in the making – a feeling that was palpable in the excitement of the crowd and the pride emanating from the many Estonians in attendance.

For Estonia, a small nation with a outsized musical heritage, seeing its festival orchestra and choir triumph on one of the world’s grandest stages was an immense source of pride. The phrase “cultural diplomacy” was not an abstraction here; it was lived experience, as a piece of Estonia’s soul was communicated to the wider world through music. As Ambassador Prikk observed, presenting Arvo Pärt’s genius at Carnegie Hall is arguably the highest honor for the country’s culture. By evening’s end, it felt not only like an honor, but a resounding success. The hall was united in applause, and for a moment, New York City itself seemed to join in celebrating Pärt at 90.

Perhaps the most beautiful lesson of the night was that Arvo Pärt’s music – though deeply connected to his faith and Estonian identity – speaks in a universal language of peace, sorrow, and hope. It can mesmerize a midtown Manhattan audience just as easily as it can move listeners in Tallinn or Tokyo. The Estonian Festival Orchestra and friends brought that truth to life. In doing so, they honored Arvo Pärt in the best possible way: by letting his “voice” be heard with clarity and devotion on a world stage. The result was pure inspiration – a concert that affirmed how music, at its finest, bridges nations and touches the human spirit.

This concert was made possible, in part, by the endowment fund for choral music established by S. Donald Sussman in memory of Judith Arron and Robert Shaw. The Estonian Philharmonic Chamber Choir thanks the Estonian American Nation Council (EANC) for their support of this performance.

.png)

.png)

.png)