Estonians would stand and sing it with pride, even in the face of foreign rulers – a poignant reminder that their love for Isamaa (fatherland) could not be silenced.

From Lydia Koidula’s Poem to National Awakening Anthem

“Mu isamaa on minu arm” has its roots in Estonia’s Great National Awakening of the 19th century. The lyrics originate from a poem by Lydia Koidula, a beloved poet who gave voice to Estonians’ growing national consciousness under czarist rule. In 1869, Koidula’s poem was first set to music by Aleksander Kunileid and performed at Estonia’s inaugural Song Festival in Tartu. This first Laulupidu (song celebration) was a landmark event where choirs from across the country sang in their native tongue – a bold cultural statement at a time when German and Russian influences dominated. “Mu isamaa on minu arm,” with its heartfelt pledge of eternal love for Estonia (“Never shall I leave you, even if I die a hundred deaths…”), resonated deeply with festival-goers. Alongside other patriotic songs like “Sind surmani” (“Till Death”) and the future national anthem “Mu isamaa, mu õnn ja rõõm,” Koidula’s verses stirred pride and hope in the Estonian people. The song’s early popularity at that 1869 celebration signaled how music could unite a nation that still lacked political freedom.

By the early 20th century, “Mu isamaa on minu arm” was a well-known choral piece, emblematic of Estonia’s yearning for self-determination. But its greatest chapter was yet to come. In 1944, as World War II raged and Estonia was caught between Nazi and Soviet forces, composer Gustav Ernesaks created a new musical setting for Koidula’s poem. Ernesaks – often called the “father” of Estonian choral music – was determined to keep Estonia’s song tradition alive through the darkest times. His poignant melody gave “Mu isamaa on minu arm” fresh emotional power, like a prayer for the homeland’s survival. When the war ended and Estonia found itself occupied by the Soviet Union, Ernesaks’s version of the song was introduced at the first post-war Song Festival in 1947. In a festival otherwise filled with Soviet propaganda songs, this new rendition of “Mu isamaa on minu arm” stood out as a rare tribute to Estonia itself. Under Stalin’s watchful eye, thousands of Estonians softly sang “My fatherland is my love” – an emotional high point that moved many to tears. The song instantly became a symbol of national pride. From 1947 onward, it became tradition for “Mu isamaa on minu arm” to be the finale of every Song Festival, with massed choirs and audiences singing it in unison. In those moments, despite the Soviet flags flying overhead, Estonians could feel united as one nation.

The Forbidden Song That Defied an Empire

Almost as soon as “Mu isamaa on minu arm” gained popularity in the late 1940s, Soviet authorities grew wary of its patriotic message. The lyrics spoke unabashedly of love and loyalty to Eestimaa (the Estonian land), at a time when Moscow insisted that Soviet republics shed their national identities. By the 1950s, the occupiers banned the song from public performance – it was deemed too nationalist, too evocative of Estonia’s independent past. At official song festivals, the beloved tune was struck from the program, and choirs were forbidden from singing it. But suppressing a song that lived in people’s hearts proved more difficult. Estonians kept the flame alive quietly; they hummed the melody in private and taught it to their children as a sacred heirloom. “Mu isamaa on minu arm” became underground cultural resistance – an unofficial national anthem that everyone knew but could not publicly acknowledge.

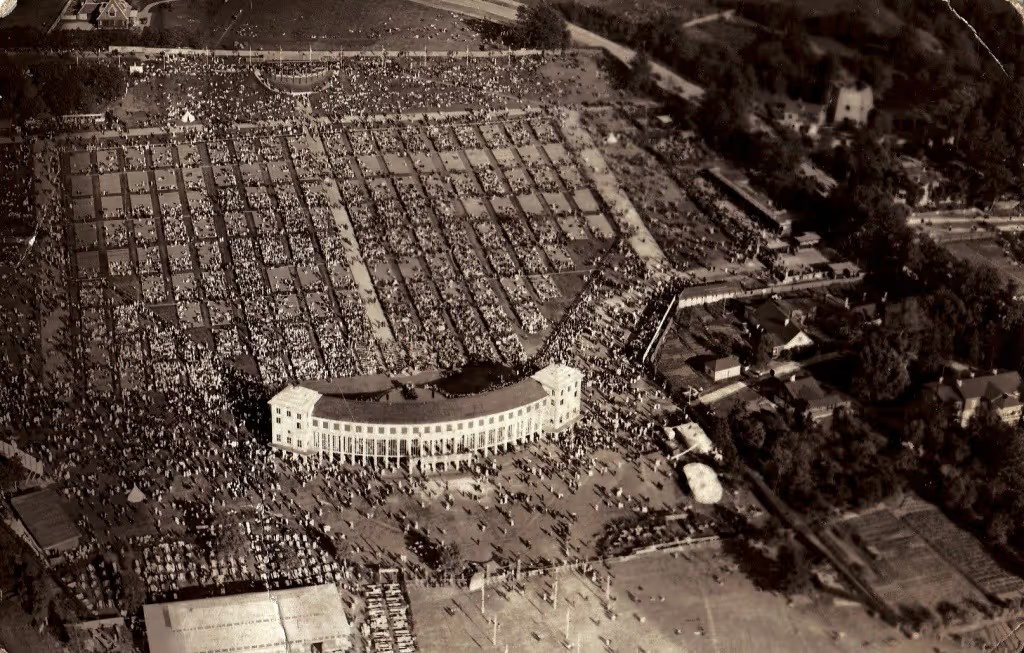

By the 1960s, a cultural thaw and rising Estonian assertiveness set the stage for a remarkable confrontation. In 1969, Estonia was preparing to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the Song Festival. Soviet officials allowed the centennial festival to go forward – they knew the event was too important to cancel – but strictly censored the repertoire. “Mu isamaa on minu arm” was explicitly forbidden from the song list. Yet on the final day, after the formal program had ended, the Estonian choirs and 100,000-strong audience refused to disperse. In an electrifying moment of unity, they struck up “Mu isamaa on minu arm” again – and again. No conductor was on stage, no orchestra accompanied them, but a sea of voices sang from the depths of their hearts. Soviet officers panicked: they ordered people to leave and even sent in a brass military band to drown out the singing. But the crowd only sang louder, repeating the song multiple times. “If 20,000 people start to sing one song, you cannot shut them up,” one participant recalled. Indeed, a mere band was no match for tens of thousands of determined Estonians. The spontaneous choir simply overpowered the noise, “overpowering a Soviet military orchestra that tried to drown them out”. Faced with this peaceful rebellion, the authorities had no choice but to relent – incredibly, they even invited Gustav Ernesaks himself on stage to conduct the final encore, in a face-saving attempt to pretend it was all officially allowed. The crowd’s victorious cheers left no doubt: the song belonged to the people. After that day, “Mu isamaa on minu arm” was never forbidden again”. It had earned its place through the courage of those singers in 1969. Estonians came to call it their song – the anthem of their hearts during the long Soviet night.

This dramatic 1969 episode proved how powerful music could be in sustaining a nation’s spirit. The sight of an entire singing nation defying an empire became legendary, and it foreshadowed a larger awakening on the horizon. As one journalist noted, this choral act of resistance laid the groundwork for the Singing Revolution (link to a film about it) to come. In the late 1980s, when Estonians once again gathered en masse to demand freedom, songs like “Mu isamaa on minu arm” were vital inspiration. During those Singing Revolution years (1987–1991), huge crowds would link arms at the Tallinn Song Festival Grounds, singing banned patriotic tunes under the noses of Soviet officials. “Mu isamaa on minu arm”, with its gentle melody and resolute words, was always among the repertoire – a comforting reminder of past perseverance. Alongside newer protest songs, it helped galvanize the people’s unity and resolve, reassuring them that no matter the oppression endured, the love of fatherland would prevail. When Estonia finally regained independence in 1991, “Mu isamaa on minu arm” rang out triumphantly once more. Many wept as they sang it, remembering those who kept the song alive through the darkest years.

A Living Legacy: Estonia’s Beloved Unofficial Anthem

Today, “Mu isamaa on minu arm” remains an indelible part of Estonian culture, inseparable from the Song Festival tradition and the national story. At each Laulupidu (held every five years), the program concludes with this song as the grand finale: thousands of singers on stage and in the audience join together, tears in their eyes, to declare their love for their homeland. The melody begins softly, then swells as voice after voice joins in, until a vast choir of Estonians – young and old, from all over the country and the diaspora – is singing as one. In those moments, time seems to bridge past and present. Listeners recall how their parents and grandparents sang “Mu isamaa on minu arm” in more perilous times, and how the song became a lifeline for the nation’s identity. Foreign visitors, even if they don’t understand the Estonian words, often feel chills witnessing the overwhelming emotion this unofficial anthem evokes.

Though Estonia’s official national anthem (“Mu isamaa, mu õnn ja rõõm”) has been restored and proudly sung since independence, “Mu isamaa on minu arm” holds a special, almost sacred status. It is a musical bond between generations – from Lydia Koidula’s 19th-century optimism to Gustav Ernesaks’s steadfast leadership in the 20th century, and onward to the free Estonia of today. The song’s message of unconditional love for the homeland continues to resonate in a world where Estonians are free to sing it at the top of their lungs. In Tallinn, a bronze statue of Gustav Ernesaks now sits at the Song Festival Grounds, gazing out over the massive outdoor amphitheater where this miracle of song occurs. Each time “Mu isamaa on minu arm” is sung by the roaring multitude, one can imagine the spirit of Ernesaks and Koidula smiling in approval.

Lyrics as sang today:

Lydia Koidula / Aleksander Kunileid (Saebelmann)

Mu isamaa on minu arm,

kel südant annud ma.

sull’ laulan ma, mu ülem õnn,

mu õitsev Eestimaa!

Su valu südames mul keeb,

su õnn ja rõõm mind rõõmsaks teeb,

mu isamaa,

:,: mu isamaa! :,:

Mu isamaa on minu arm,

ei teda jäta ma.

Ja peaks sada surma ma

see pärast surema!

Kas laimab võõra kadedus,

sa siiski elad südames,

mu isamaa,

:,: mu isamaa! :,:

Mu isamaa on minu arm,

ja tahan puhata,

su rüppe heidan unele,

mu püha Eestimaa!

Su linnud und mull’ laulavad,

mu põrmust lilled õitsetad,

mu isamaa,

:,: mu isamaa! :,:

In the end, “Mu isamaa on minu arm” is far more than just a song. It is the sound of the Estonian soul – a love song to the land that sustained its people through hardship and inspired them to reclaim their freedom. From its humble debut in 1869 to its role as the unofficial anthem under Soviet oppression, this melody has carried the hopes of a nation. Even today, whenever Estonians join together to sing “My fatherland is my love, to whom I have given my heart”, one can feel the unbroken thread of history and the profound unity of a people who, through song, kept their identity alive. In the story of Estonia, Mu isamaa on minu arm will forever remain a shining emblem of patriotism, resistance, and the enduring love between a nation and its homeland.

.png)

.png)

.png)