Sweden, through agents known as Birkarls, also entered this competition for the north by the 14th century, seeking to profit from the fur trade and fishing. By the late 1500s, all three powers – Denmark-Norway, Sweden, and Russia – vied for control of the lucrative Arctic frontier. Each aimed to secure trading rights (especially in stockfish (dried cod) exports and fur) and, crucially, to gain a coastline on the Arctic Ocean.

This medieval contest set the stage for a “race for the Arctic coast.” Norway (then in union with Denmark) established early footholds along the far northern coast; a Norwegian fortress was built at Vardø in 1306, symbolically anchoring Norway’s claim to the Barents Sea shores. Sweden, whose heartland was farther south, was slower to reach the true Arctic. However, by the late 16th century, Swedish King Karl IX ambitiously pushed northward. In 1595, Sweden signed a peace with Russia and, seizing the moment, extended its claimed border into the far northeast – even attempting to give Swedish-ruled Finland an “unobstructed access” to the Arctic coast of what is now Norway. This move encroached on territories long claimed by Denmark-Norway, setting the stage for conflict.

The 1613 Treaty of Knäred and Norway’s Arctic Edge

By the early 17th century, Sweden’s Arctic ambitions alarmed the Danish-Norwegian crown. King Karl IX of Sweden had started taxing settlers in Finnmark (the far north of Norway) in an effort to secure a Swedish outlet to the Arctic Ocean. In response, Denmark-Norway’s King Christian IV went to war – a conflict known as the Kalmar War (1611–1613) – fundamentally a fight for the “Northern Cap” of Scandinavia. Though battles raged farther south (around the fortress of Kalmar in Sweden), the war’s key stakes were in the Arctic. The outcome came with the Peace of Knäred signed in January 1613, which decisively curbed Sweden’s northern aspirations. By this treaty, Sweden renounced all claims to Finnmark and the northern coast, formally recognizing Danish-Norwegian sovereignty over those far northern territories. In effect, Norway’s exclusive outlet to the Arctic Ocean was preserved, thwarting Sweden’s attempt to reach those waters. Contemporary accounts noted King Christian’s triumph: Sweden had to relinquish its claim to Finnmark and any access to the Arctic Ocean; the “Northern coastline” was henceforth firmly assigned to Dano-Norwegian rule.

The Treaty of Knäred was a turning point. It left Sweden landlocked to the south of latitude ~68° N, unable to ever touch the Arctic Ocean directly. Norwegian Finnmark, by contrast, remained a part of the Danish-Norwegian kingdom, wrapping around the top of the Scandinavian peninsula. This outcome – essentially cutting off Sweden (and Swedish-controlled Finland) from the Arctic seas – has endured into the present map of Europe. Notably, even Sweden’s port of Älvsbyn on the North Sea, briefly taken in the war, had to be ransomed back at great cost, underscoring Sweden’s isolation from the Atlantic/Arctic ocean routes. After 1613, any Swedish influence in the high north had to be indirect. For example, Swedish traders could still travel and trade in the north, but sovereignty belonged to Norway. The Arctic coast became Norway’s alone in mainland Scandinavia, a status guarded jealously in subsequent centuries.

Drawing Borders: 18th- and 19th-Century Treaties

Though 1613 confirmed who owned the northern coast, the exact borders in the Arctic remained vague for a long time. For over a century after Knäred, the inland frontier in Lapland was not clearly delimited – it was, in effect, a multinateral “commons” where Sámi could move freely and multiple crowns claimed taxation rights (the fellesdistrikt or common district). Not until the Treaty of Strömstad in 1751 did Denmark-Norway and Sweden draw a firm border all the way through the interior north. This treaty formally partitioned the remaining shared Lapland territories between the two kingdoms. Norway gained large interior tracts (including Karasjok and Kautokeino in today’s Finnmark), while Sweden took areas further south in what is now Swedish Lapland. A special addendum, the Lapp Codicil of 1751, ensured that the Sámi people could continue crossing the new border with their reindeer herds – an important recognition of indigenous rights, albeit one that later faced restrictions. By fixing the Norway-Sweden boundary from the southern fjords up to the 69th parallel, the 1751 agreement ensured that Norway’s territory definitively “wrapped around” Sweden in the north, connecting Norway’s Nordland/Troms coast to Finnmark without interruption. Sweden was left with no sea access above the Gulf of Bothnia.

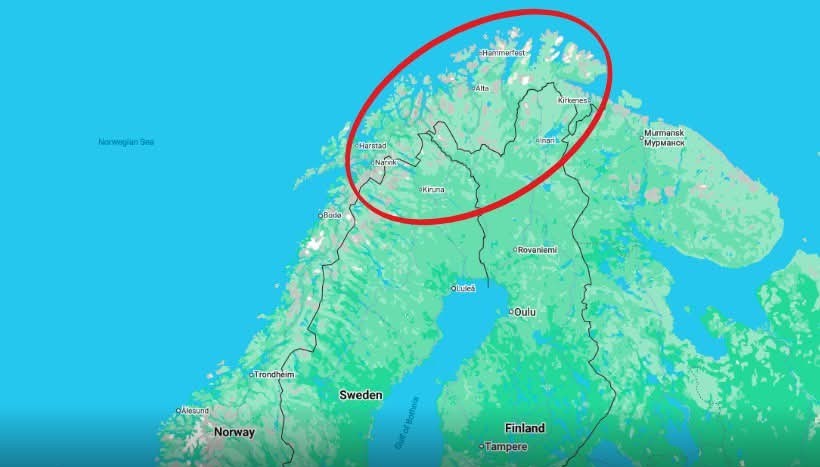

A few decades later, geopolitical upheaval again reshaped the north. In 1809, Sweden lost the entirety of Finland to the Russian Empire. Suddenly, Sweden no longer bordered Norway’s far north at all – instead, it was Imperial Russia (via its Grand Duchy of Finland) that now met Norway’s border in Lapland. This new reality required another round of border-making. In 1826, Norway (then in union with Sweden, but governing its own territories) negotiated a treaty with Russia to finally demarcate the Norway–Russia frontier in the Arctic. The 1826 Treaty of Saint Petersburg drew a line through the previously unpartitioned eastern Lapland, from a point on the Tana River to the Arctic coast, dividing the last “no man’s land” between Norway, Russia, and Russian-controlled Finland. Norway ceded any remaining claims to the Kola Peninsula (to Russia) but secured a sizeable strip of land on its side of the Pasvik River, extending its territory eastward. The treaty notably created the present-day “Finnmark wedge”: Norway’s border juts eastward to meet Russia on the Varanger fjord, forming a wedge that separates Finland from the Arctic Ocean. At the very end of this border, a small kink was drawn so that an Orthodox chapel (the Boris Gleb chapel) would remain on the Russian side – a curious twist reflecting Russia’s insistence on keeping that sacred site within its territory. With this final settlement, the map was set: Finland (under Russian rule) was landlocked, and Norway’s dominion stretched unbroken along the entire Atlantic and Barents Sea coast from its southern tip at Lindesnes up to the Russian frontier near Kirkenes.

By the mid-19th century, Norway’s northern border was thus firmly established. Even after Norway gained independence from Sweden in 1905, those borders did not change. The result of these historical treaties is the unusual shape of Norway today – a long, curving nation that wraps around the top of both Sweden and Finland, monopolizing access to Arctic waters in mainland Europe. This is evident on any map: at the tripoint near Treriksröset, a concrete cairn marks where Norway, Sweden, and Finland meet at a lake in the high tundra. From that point, the Norwegian border swings east and then south, ensuring that Sweden’s and Finland’s northernmost corners stop just short of the sea.

.jpg)

Finland’s Lost Path to the Arctic

One country did briefly alter this Arctic access picture: Finland. After gaining independence from Russia in 1917, Finland sought its own window to the Arctic Ocean. In the Treaty of Tartu (1920) following the Russian Civil War, the new Soviet state ceded to Finland a small Arctic coastline: the Petsamo (Pechenga) region on the Barents Sea. This narrow panhandle, about 50 km wide, gave Finland a port on the Arctic: Petsamo and its harbor at Liinahamari. For the first time, Finland had direct access to Arctic shipping lanes – an economic and strategic boon. In fact, between the world wars, adventurous motorists could drive a “Arctic Ocean Highway” from Helsinki up to the ice-free port of Petsamo, and Finland even envisioned itself as an Arctic maritime nation.

However, Finland’s Arctic coast was short-lived. In World War II, the Soviet Union invaded and occupied Petsamo, and in the 1944 armistice (and confirmed by the 1947 Paris Peace Treaty) Finland was forced to cede Petsamo permanently to the USSR. Thus, Finland’s brief window to the Arctic Ocean closed – the Petsamo panhandle was absorbed into Russia’s Murmansk region, and Finland was again landlocked to the north. Today, the Finnish–Russian border in the north ends at a lonely tripoint cairn in the Pasvik river valley, where Norway’s easternmost tip again wedges between them. A visitor to that remote spot can stand with Finland behind, Russia to one side, and Norway’s Arctic hills to the other – a powerful reminder of how geography and history intertwined to leave Sweden and Finland without a seashore in the Arctic.

In sum, by the late 20th century the historical pattern reasserted itself: only Norway (and Russia) possess Arctic coasts in mainland Europe. Sweden never gained one, and Finland’s 20-year experiment with an Arctic coastline ended in loss. These outcomes stem directly from the treaties and power struggles of earlier centuries – especially Norway’s success in maintaining its “Arctic edge” through diplomatic and military victories.

Norway’s Arctic Advantage in the Modern Era

Fast-forward to today, and Norway’s unique geography grants it significant advantages – and responsibilities – in the Arctic. Norway’s Arctic coastline (stretching through Troms og Finnmark county and around the North Cape) makes it one of only five countries with a shoreline on the Arctic Ocean (the others being Russia, Canada, the United States, and Denmark via Greenland). Moreover, Norway exercises sovereignty over the Svalbard Archipelago (granted by the 1920 Svalbard Treaty), extending its reach to 80° N latitude. In contrast, Sweden and Finland remain Arctic nations without Arctic coasts: both have territories extending into the Arctic Circle (with cold, northern climates and midnight sun in places like Kiruna, Sweden or Nuorgam, Finland), but any seaborne ambitions must be pursued in partnership with coastal neighbors.

Norway’s status is further distinctive in that it is an Arctic state that is not a member of the European Union. While Denmark (via Greenland), Finland, and Sweden link the EU directly to Arctic affairs, Norway engages as an independent player closely allied to the EU but outside its formal structures. This has positioned Norway as a critical bridge between the EU and the Arctic region. In fact, the European Parliament recently highlighted Norway as a “key EU and NATO ally” in Arctic matters, emphasizing Norway’s importance as a major supplier of natural gas to Europe and a linchpin in defense cooperation in the High North. Norway’s vast offshore gas fields in the Norwegian and Barents Seas have become even more vital to Europe’s energy security in recent years, especially as EU countries seek alternatives to Russian gas. Although not in the EU, Norway through the European Economic Area participates in many EU programs, and its alignment with European sanctions and policies (for example, after Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine) underscores its role as a like-minded partner. In Arctic strategy, Norway often finds itself at the center of EU attention – the EU’s Arctic Policy documents frequently cite collaboration with Norway on sustainable development, energy, and research as essential. In short, Norway’s Arctic coastline and resource wealth make it a cornerstone of regional cooperation, even as it remains formally outside the EU.

By virtue of its geography, Norway also acts as a gateway to the Arctic for its Nordic neighbors. Important infrastructure underscores this: for instance, the ice-free Norwegian port of Narvik has long been critical for Swedish iron ore exports (allowing year-round shipping which Sweden’s Gulf of Bothnia ports cannot support in winter). Similarly, Finland has eyed Norway’s northern harbors – such as Kirkenes – as potential outlets to the Arctic Ocean. There have been ongoing discussions of building an “Arctic railway” from Finland to a Norwegian deep-water port, which would give Finnish industry direct access to Arctic maritime routes. While such plans remain under study, they highlight how Finland and Sweden rely on Norway’s coastline (or Russia’s, in less ideal scenarios) to participate in Arctic maritime commerce. Norwegian policy generally welcomes this regional cooperation, seeing it as beneficial for northern development. However, Norway’s sovereign control means it sets the terms – for example, any new rail or road links would be bilateral projects subject to Norwegian environmental and security considerations.

%20(1).jpg)

Arctic Council and Nordic Cooperation

The Arctic Council – the premier intergovernmental forum for Arctic issues – illustrates the differing positions of Norway, Sweden, and Finland. All three are full members of the Council (as are the other five Arctic nations: Russia, Denmark, Iceland, Canada, and the US). Within this body, they work together on environmental protection, Indigenous affairs, scientific research, and sustainable development in the far north. However, Norway often has a special role due to its coastal status. Many Arctic Council working groups (on marine protection, shipping, fisheries, etc.) rely on the expertise of the Arctic littoral states, and Norway is the only Nordic country in that category besides Denmark (Greenland). In practice, this means Norway takes lead on issues like Arctic Ocean search-and-rescue coordination, fisheries management, and offshore resource guidelines, whereas Sweden and Finland contribute more on areas like research, climate policy, or land-based environmental concerns in the Arctic. All three countries champion Indigenous rights (the Sámi span across Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Russia), and all support keeping the Arctic peaceful and cooperative.

One subtle difference lies in the role of the European Union. Sweden and Finland, as EU members, often coordinate to amplify the EU’s voice in Arctic affairs. They have welcomed stronger EU engagement in the region, seeing the EU as a partner in funding research, infrastructure, and climate resilience in the north. Sweden’s official Arctic Strategy explicitly “welcomes stronger EU involvement in the Arctic”, affirming the EU as an important partner alongside the Arctic states. Finland’s Arctic Policy similarly states that “for stability and sustainable development in the Arctic, the European Union is of key importance”. Both countries leverage their EU membership to shape the Union’s Arctic policies – for instance, pushing for an EU Arctic Ambassador and Arctic information center, or using EU platforms to address issues like black carbon pollution in the Arctic.

Norway, on the other hand, while closely aligned with EU values, navigates Arctic diplomacy on a sovereign footing. Norway’s Arctic policy emphasizes cooperation through the Arctic Council and with partners like the US and Canada, without an overt EU dimension. In Norway’s latest High North strategy (2025), the focus is on national interests and allied coordination (particularly NATO allies), and it does not directly reference the EU’s Arctic role. This doesn’t mean Norway is adverse to the EU in the Arctic – far from it, Norway works hand-in-hand with EU countries on science and environmental efforts. But it underscores that Finland and Sweden tend to “speak EU” in Arctic forums, whereas Norway speaks as a non-EU Arctic coastal state. A practical example is Arctic climate policy: Finland and Sweden often dovetail their Arctic climate goals with EU Green Deal strategies, while Norway, rich in oil and gas, balances its climate initiatives with its petroleum industry (often in dialogue with the EU, but as an external partner).

At the Arctic Council, these three Nordics usually present a united front despite such nuances. Notably, as of 2023–2025, Norway holds the rotating chairmanship of the Arctic Council, taking over after a challenging period (when Russia held the chair during its invasion of Ukraine). Norway’s chairship program stresses traditional Arctic Council pillars – climate, environment, oceans, sustainable development, and people of the North – aiming to keep the Council apolitical and functional. Finland and Sweden strongly support Norway’s leadership and have coordinated with Oslo to ensure the Council’s work continues despite East-West tensions. All three countries are keen to resume full Arctic Council cooperation with Russia when conditions permit, but in the interim they have continued projects among the seven western members. In this context, Norway’s non-EU status is mostly a footnote – the Nordic family works together, whether inside or outside the EU, to keep the Arctic Council effective. The greater distinction now is actually NATO membership, which all Nordic states except Sweden (pending at the time of writing) have, but which the Arctic Council formally ignores due to its non-security mandate.

.jpg)

Shipping, Fisheries, and Resource Rights in the Barents Sea

One of the most immediate consequences of Norway’s Arctic geography is control over rich fisheries and petroleum resources. Norway’s Barents Sea Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) abuts Russia’s EEZ, covering some of the most abundant fishing grounds on the planet (notably the Barents Sea cod stocks). For decades, Norway and Russia have co-managed these fisheries through bilateral agreements – a cooperative success story that continued even during the Cold War. Here, Norway’s position as a coastal state gives it exclusive rights that Sweden and Finland lack. Each year, Norwegian and Russian officials set quotas for cod, haddock, and other species in the Barents, ensuring sustainable yields. The EU (including Finland/Sweden) has no direct say in these bilateral Barents fish quotas – except to respect them – because the waters belong to Norway and Russia. This can sometimes be a point of contention: for example, EU sanctions on Russian seafood or Norway’s own restrictions can affect markets, but the resource management remains a Norway-Russia domain. Norway also controls fisheries around Svalbard, subject to the Svalbard Treaty’s non-discrimination rules, meaning EU countries can fish there but under Norwegian regulations.

As Arctic shipping routes gradually become more accessible due to climate change, Norway stands to benefit from its geography. It sits at the gateway of the Northern Sea Route (NSR) – the shipping lane along Russia’s Siberian coast. While the NSR itself is under Russian jurisdiction, any ships entering or exiting it to Europe must pass near Norway’s Nordkapp and through the Barents Sea. Norway provides port services (Kirkenes, Tromsø, etc.) that could serve as hubs for trans-Arctic trade in the future. In addition, Norway has worked through the Arctic Council to develop guidelines like the Polar Code for safe shipping, and has hosted the Arctic Shipping Best Practice Information Forum. In practical terms, Finland and Sweden lack direct access to these emerging routes – Finland is investing in icebreaker technology and proposing new rail links to the Arctic, but without a seaport of its own on the Arctic Ocean, it must collaborate with Norway or Russia for any Arctic maritime corridor. Sweden’s northern ports (on the Gulf of Bothnia) are not in the Arctic Ocean and also face heavy ice in winter, limiting their utility for Asia-Europe routes. Thus, Norway is uniquely positioned among the Nordics to capitalize on any future boom in Arctic shipping, whether it be servicing transit traffic or asserting its interests in international negotiations about navigational freedom in Arctic seas. Oslo’s policies reflect this: Norway prioritizes safe, environmentally sound shipping and has beefed up its Coast Guard presence in the north to monitor increasing vessel traffic.

Another arena is offshore energy and mineral exploration. Norway, thanks to its Arctic coast, holds rights to vast subsea resources. The country has already developed the Snøhvit natural gas field in the Barents Sea (which feeds Europe’s only LNG export terminal above the Arctic Circle), and continues exploratory drilling for oil and gas farther north. In 2010, Norway and Russia resolved a 40-year maritime boundary dispute in the Barents Sea, splitting a formerly contested area into clear zones. This allowed Norway to open new acreage for exploration on its side – an opportunity Sweden and Finland, with no continental shelf in the Arctic Ocean, simply do not have. Instead, Sweden and Finland’s mining interests in the Arctic are on land (iron ore, copper, nickel, phosphate, and rare earth elements in northern Fennoscandia). They too are important for the global resource supply, but when it comes to offshore oil, gas, and even seabed minerals (like polymetallic nodules or potential deep-sea mining), Norway is the Nordic representative in that aspect of Arctic resource geopolitics. Notably, Norway balances resource development with environmental concerns – there is significant domestic debate about how far north drilling should go, given the fragile Arctic ecosystem and Norway’s climate commitments. The Norwegian government often highlights “sustainable economic development” as a key Arctic priority, aiming to reconcile its role as a major petroleum exporter with stewardship of Arctic nature. Sweden and Finland, through the EU, sometimes urge caution on Arctic oil and gas (the EU’s Arctic policy even contemplates no new oil in the Arctic). Norway tends to respond that any Arctic oil & gas must be developed responsibly and that Norway – with high environmental standards – is preferable to unregulated development elsewhere.

Security and Strategy in the High North

The strategic landscape of the Arctic has also evolved with Norway’s geography and the changing affiliations of its neighbors. During the Cold War, Norway was the only Nordic NATO member bordering the Soviet Union. The Norwegian-Russian border in the far north, near Kirkenes, was a quiet but critical front: the Kola Peninsula on the Russian side hosts the Soviet/Russian Northern Fleet, including nuclear submarines, making the adjacent Norwegian Sea and Barents Sea a naval strategic arena. Norway walked a careful line – a loyal NATO member (since 1949) but one that practiced restraint in the north (for example, Norway long prohibited foreign NATO bases on its soil in peacetime and limited NATO exercises in Finnmark, to avoid provoking Moscow). Meanwhile, Sweden and Finland were neutral (or militarily non-aligned) during the Cold War, which meant the Nordic far north was partly buffered from superpower tensions. The Arctic Council’s formation in 1996, which included Russia, was in that spirit of keeping the region low-tension and cooperative.

However, recent years have transformed the security picture. With Russia’s more assertive military posture (especially after 2014 and 2022 in Ukraine) and Finland and Sweden’s decisions to join NATO (Finland in 2023, Sweden in 2024), the entire European Arctic (bar Russia) is now in the NATO alliance. “With Sweden and Finland as new members of NATO, the Arctic region becomes more prominent for the Alliance,” notes a 2024 Atlantic Council analysis. In NATO parlance, the “High North” is now recognized as a crucial theater for collective defense. Traditionally, NATO left Arctic security largely to Norway, Denmark, and the US, avoiding overt Alliance involvement to minimize friction with Russia. That is changing: NATO has signaled it must “increase its presence in the Arctic” given Russia’s military build-up in the north and also China’s growing interest. For Norway, this is a double-edged development. On one hand, having its Nordic neighbors in NATO strengthens security cooperation – Norway, Sweden, and Finland can now fully integrate defense planning for northern Europe. Indeed, Norway’s 2025 High North strategy explicitly welcomes the fact that “with Sweden and Finland in NATO, Nordic cooperation in the north will be further strengthened”, reinforcing regional stability. Joint surveillance, air patrols, and cold-weather training among the Nordic allies are ramping up. Norway, as the long-experienced NATO member, is effectively guiding Finland and Sweden into Arctic-focused defense coordination. For example, Finland contributes land forces suitable for Arctic warfare, Sweden brings advanced air and naval assets (like submarines) in the Baltic and potentially North Atlantic, and Norway continues to focus on maritime surveillance and deterrence in the Norwegian and Barents Seas. Together, the Nordic NATO countries are creating a more seamless defense posture stretching from the Baltic Sea to the Barents.

On the other hand, a fully NATO-aligned Nordic region may heighten tensions with Russia in the Arctic. Moscow has viewed NATO’s expansion northward with suspicion, and its military activities around the Kola Peninsula and Arctic airspace have increased. Norway, while firmly committed to NATO, remains eager to keep the Arctic as a “low tension” zone if possible. It often emphasizes that NATO’s interest in the Arctic is defensive and proportional. Notably, even after Finland joined NATO, Norway continued bilateral engagements with Russia on practical matters like fishery management and border logistics – signaling that not all cooperation is frozen. Still, the Arctic Council has been strained since Russia’s war in Ukraine; meetings above the senior-official level were paused, and projects carried on without Russian participation in 2022–2023. Under Norway’s chairmanship, some limited communication has resumed, but the West’s Arctic strategy now inevitably includes hard security considerations alongside the Council’s cooperative work. In parallel, the Nordic countries coordinate in other forums such as the Barents Euro-Arctic Council and NORDEFCO (Nordic Defense Cooperation) to maintain dialogues that include Russia (in the former) or at least to align themselves (in the latter).

In summary, Norway’s unusual Arctic border – snaking around Sweden and Finland – is not just a cartographic curiosity; it is the product of a deep history that has given Norway a special role in the north. It has shaped everything from medieval tax payments to 17th-century wars, from 18th-century treaties to 21st-century strategic alliances. Today, Norway’s coastline grants it influence over Arctic shipping lanes, fisheries, and energy – and also burdens it with front-line responsibilities for NATO in a new era of great-power rivalry in the Arctic. Meanwhile, Sweden and Finland, though lacking direct Arctic coasts, have found other ways to stake their presence: through the EU’s Arctic initiatives, scientific research, and now their participation in NATO’s Arctic posture. Their memberships in the EU and NATO intersect with Arctic strategy in complementary fashion to Norway’s approach. Finland’s foreign ministry summed it up well in 2025: “The other Nordic countries, Canada and the United States are Finland’s close allies and partners in both NATO and the Arctic Council.” Furthermore, “for stability and sustainable development in the Arctic, the European Union is of key importance”. This reflects a holistic strategy where Finland (and Sweden) leverage both NATO and EU frameworks, whereas Norway continues to lead as a non-EU Arctic coastal state tightly integrated with its allies.

Official documents and treaties underpin these narratives: from the Treaty of Knäred (1613) confirming Norway’s hold on Finnmark, to the Treaty of Strömstad (1751) and the Russo-Norwegian treaty of 1826 drawing today’s borders, to modern Arctic strategies issued by Nordic governments. All attest to the enduring importance of that sliver of Norwegian soil at Europe’s crown. It may look like a quirk of geography that Norway’s map wraps around its neighbors, but it is fundamentally a story of power, negotiation, and adaptation through history. And as the Arctic becomes ever more significant – due to climate change, new shipping routes, and global strategic interest – this historical border arrangement continues to have profound consequences for Northern Europe and the world.

.png)

.png)

.png)