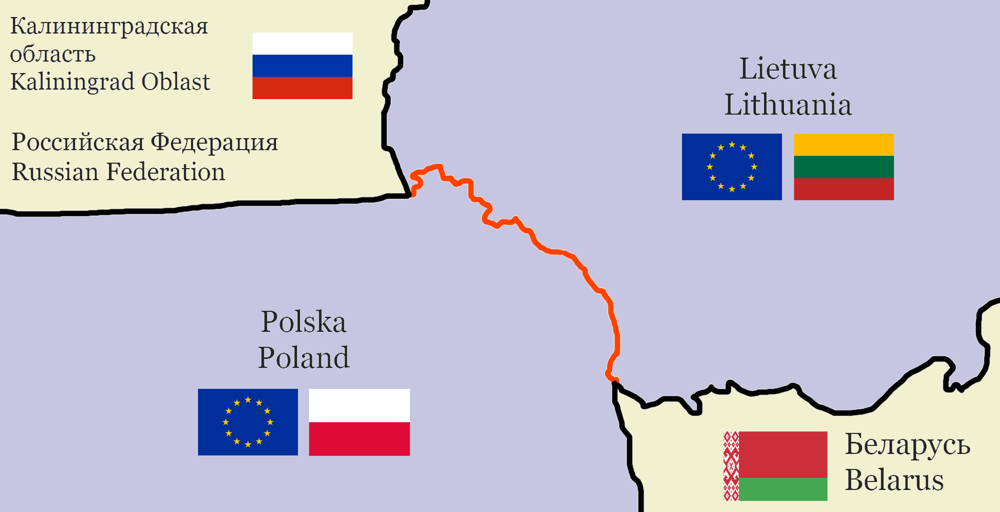

On one side lies Kaliningrad – a heavily armed Russian enclave on the Baltic Sea – and on the other side is Belarus, Moscow’s close ally. In a conflict, a move by Russia to seize this narrow corridor could cut off Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia from overland reinforcement, isolating over six million people behind a hostile blockade. For NATO and the European Union, the Suwałki Gap is truly a lifeline to the Baltic region – and a potential choke point that keeps military planners awake at night.

A Strategic Lifeline Between East and West

Geographically, the Suwałki Gap is a sparsely populated stretch of rolling countryside, forests, and lakes centered near the Polish town of Suwałki. It was little more than a quiet frontier until the late 20th century, but history and geopolitics have thrust it into the spotlight. The modern border was drawn in 1920 after World War I, and during the Cold War it faded into obscurity – Poland and Soviet Lithuania were then on the same side of the Iron Curtain. This changed dramatically after the Soviet Union’s collapse. When Poland joined NATO in 1999 and Lithuania (along with Latvia and Estonia) followed in 2004, the Suwałki Gap suddenly became the only overland route linking the Baltic allies to Western Europe. At the same time, Russia lost direct land access to Kaliningrad, its westernmost territory, turning that oblast into a military outpost cut off from the mainland.

Kaliningrad’s presence is a big reason the Suwałki Gap matters. This small Russian exclave on the Baltic coast is bristling with military assets – it hosts the port of Baltiysk, Russia’s only year-round ice-free Baltic Sea port and the headquarters of the Russian Baltic Fleet. From Kaliningrad, Russia projects power with warships, advanced missiles, and air forces, keeping NATO on edge. Yet Kaliningrad is isolated; it relies on a tenuous transport link via Lithuania and Belarus or by sea and air. The Suwałki Gap is the shortest land bridge to connect Kaliningrad with Belarus (and thus Russia proper). Moscow has long recognized the gap’s value – in the 1990s, Russia even tried to negotiate an “extraterritorial corridor” across this area to move goods and people to Kaliningrad, but Poland, Lithuania and the EU flatly refused. In 2022, amid heightened tensions over Russia’s war in Ukraine, Lithuania enforced EU sanctions by restricting certain Russian freight traffic to Kaliningrad, leading to a sharp exchange of threats. That incident, though resolved, underscored how even in peacetime the Suwałki corridor is a pressure point between Russia and NATO, as well as between Russia and the EU.

From NATO’s perspective, the Suwałki Gap is often described as the alliance’s “Achilles’ heel” on its eastern flank. Only a pair of small highways and some country roads run through this corridor. All of it lies within reach of Russian forces from two sides – Kaliningrad to the north and Belarus to the south. Military planners fear that in a crisis or war, Russia could rapidly squeeze this gap from both directions, blocking the roads and severing NATO’s access to the Baltic States. If that happened, Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia would be landlocked behind enemy lines, reachable only by air or via the Baltic Sea. In essence, the Gap’s loss would isolate NATO’s Baltic members, making it vastly harder to come to their aid in time. One NATO commander famously remarked that holding the Suwałki corridor could be the difference between defending the Baltics or losing them in a matter of days.

For Russia, conversely, seizing the Suwałki Gap would be a strategic windfall. It would physically link Kaliningrad with Belarus (and Russia), creating a contiguous zone of control along NATO’s border. This land bridge would strengthen Russia’s position in the Baltic Sea region and simultaneously cut off NATO’s northeastern frontier. Russian military writings have often noted Kaliningrad’s vulnerability – wedged between NATO countries – and how closing the gap would remedy that at NATO’s expense. It’s a scenario that deeply worries the Baltic nations and their Nordic neighbors. They know that if the Baltics were cut off, their survival in a conflict would be in grave peril. A Lithuanian defense planner once put it bluntly: “If the Suwałki Gap is closed, the Baltic States are lost.” For this reason, maintaining control of that corridor in any future crisis is absolutely pivotal for NATO.

.jpg)

NATO’s Security Challenge: Weak Link or Strengthened Flank?

The Suwałki Gap poses a thorny security challenge for NATO, the EU, and the wider Nordic-Baltic region. During the past decade, it has been a focus of countless war games, military exercises, and strategic debates. At one point, Western defense analysts routinely called it NATO’s “weak link” – a spot where the alliance was most vulnerable to a sudden Russian thrust. After Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014, these worries spiked dramatically. The full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022 only reinforced that fear: if Moscow was willing to brutally violate international law and attack its neighbor, could the Baltic nations be next in line? Baltic leaders, recalling their own countries’ long history under Soviet occupation, take such threats very seriously. Since 2022, Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia have all declared states of high alert in their defense planning and begun boosting their military budgets towards an extraordinary 5% of GDP – among the highest levels in the world. They are effectively saying: we will do whatever it takes to avoid being overrun.

At the same time, Russia’s war in Ukraine has significantly degraded Russia’s military and drained its resources. This paradoxically offers a measure of reassurance for NATO in the near term. With Russian forces bogged down and bloodied in Ukraine, few believe Moscow could easily spare the troops or morale to attack NATO territory imminently. Indeed, as of 2024, many Western officials rate a direct Russian invasion of Poland or Lithuania as unlikely while the conflict in Ukraine continues. However, “unlikely” doesn’t mean “impossible.” The chilling lesson of recent years is that the Kremlin can make reckless decisions and strategic miscalculations. No one in Tallinn, Riga, or Vilnius will ever forget that virtually no one predicted Russia would seize Crimea in mere days, or attempt a full conquest of Ukraine – until it happened. Thus NATO faces a delicate balancing act: it must not be complacent about the Suwałki Gap, even if an attack there today seems a remote risk. The cost of complacency could be catastrophic. As one NATO general warned, you prepare for the worst-case scenario before it’s on your doorstep.

Western experts and planners have sketched out how a Suwałki Gap crisis might unfold – and it’s not a pretty picture. One glaring concern is speed: Russia could launch a rapid pincer from Kaliningrad and Belarus that overwhelms the gap in a matter of hours, before reinforcements arrive. In fact, in NATO simulations, a coordinated Russian offensive was able to capture the Suwałki corridor in as little as 2–3 days, presenting NATO with a devastating fait accompli. By striking swiftly, Russia would hope to present the alliance with a done deal – a new reality on the ground that Moscow would then insist NATO accept. This is essentially the “grab the gap” scenario that keeps defense planners awake at night. If the corridor fell, NATO would then face the excruciating decision of how to respond: attempt a risky and bloody counteroffensive to reopen the gap (escalating into a full NATO-Russia war), or hesitate and perhaps lose the Baltics without a fight. Both options are nightmarish. Military exercises conducted by the U.S. and Poland underscore the stakes. In one American war game, Poland suffered an estimated 60,000 casualties in the first day of fighting as NATO forces struggled to plug the gap. A Polish-run simulation (code-named Zima-20) yielded similarly grim results: within four days, Russian units in the scenario had driven so deep that they reached the Vistula River and even threatened Warsaw. These outcomes, though hypothetical, illustrate that any battle over Suwałki would be intense and deadly for all sides. Simply put, losing the Suwałki Gap to Russian aggression would be an unspeakable disaster – not only a military defeat for NATO, but a humanitarian catastrophe for the region.

The question of political will also looms large. NATO’s founding treaty declares that an attack on one member is an attack on all, obligating a collective defense (the famous Article 5). Would NATO really go to World War III over a sparsely inhabited sliver of land in northeastern Europe? Most allies insist the answer is yes – credibility demands that every inch of NATO territory be defended. Yet adversaries have probed for doubt. In 2024, then former U.S. President Donald Trump (while campaigning) openly questioned whether America should defend certain allies he deemed insufficiently prepared, sending shivers through Baltic capitals. Such rhetoric fuels Moscow’s hopes that NATO might flinch if the cost of intervention seems too high. Some Western scholars have even speculated that the Kremlin might calculate that seizing the “empty” Suwałki corridor could go unpunished – that perhaps Washington wouldn’t risk nuclear war for a 40-mile strip of farmland. This kind of dangerous thinking is exactly what NATO’s deterrence aims to counter. Alliance officials constantly emphasize unity and resolve, precisely to ensure Moscow has no doubts about NATO’s response. The bottom line: NATO cannot allow any cracks in its commitment, because the Suwałki Gap’s security ultimately hinges on Russia’s confidence (or lack thereof) in NATO’s collective defense. Weakness or hesitation, even just perceived, could invite the very aggression everyone is desperate to prevent.

Geography and Terrain: A Difficult Battlefield

The Suwałki region’s geography is a double-edged sword – daunting for attackers, but also tricky for defenders. Unlike the open plains of central Poland, this corner of the Baltic frontier is a patchwork of thick forests, wetlands, rolling hills and small villages. In fact, about half of the land is covered by forests and lakes, with marshes accounting for an additional ~10%. Much of the area is sparsely populated wilderness. Narrow rivers twist through steep, wooded banks, and the soil in many places is soft and muddy. Local residents can attest that from early spring through late autumn, rain turns fields and unpaved paths into quagmires. By winter, heavy snow and deep frost further impede movement. This means any army trying to advance through the Suwałki Gap faces nature as an opponent as much as any human enemy. Tanks and heavy vehicles would find it tough going off the main roads: waterlogged ground can swallow up armored vehicles, and in winter some secondary roads become impassable. Even the summer of 2023, which saw Wagner Group mercenaries briefly deployed in nearby Belarus, was marked by heavy rains that would have bogged down large troop movements.

Not surprisingly, the limited infrastructure in the gap is a critical factor. Only two principal highways run north–south from Poland into Lithuania through this corridor. There are a handful of smaller paved roads and numerous dirt tracks used by farmers and loggers, but very few routes can support heavy military convoys. To make matters worse, many local bridges are old and not built for modern armored vehicles – some can only carry about 50 tons, sufficient for a Russian T-72 tank but not for a 70-ton American M1 Abrams or British Challenger tank. An advancing NATO column of heavy armor might literally face bridges that collapse under it unless reinforced. Offensive forces would likely be forced into choke points, funneled onto the few reliable roads. This “canalization” means they could end up in long, slow convoys – easy targets for air strikes or artillery. In other words, an attacker cannot easily blitz through the woods en masse; they’d have to stick to narrow corridors, which can become killing zones. This greatly favors a defender who is prepared. A relatively small defending force, if skilled and dug-in, could use mines, felled trees, and anti-tank ambushes to block roads and delay a much larger attacker. Indeed, military analysts note that Suwałki’s hilly, wooded terrain naturally lends itself to defensive tactics like ambushes and entrenchments. The plentiful cover and concealing foliage limit the usefulness of the attacker’s artillery and air support, since finding targets in the thickets is difficult. In short, the terrain “gives an advantage to the underdog on defense,” as one expert put it.

However, this same geography is a curse if the defender loses the gap initially. Should Russian troops seize control of the corridor, those forests and marshes would then work against any NATO counter-attack. The very obstacles that slow an invader would also slow liberating forces trying to push them out. Analysts warn that once occupied, the Suwałki Gap would be extremely hard to retake. Russian units could fortify the high ground, destroy bridges behind them, and use the dense terrain to conceal their own movements. NATO would face the grim prospect of assaulting well-defended positions in rough country – a costly endeavor. This mutual difficulty is why controlling the gap from the outset is so crucial. NATO’s playbook emphasizes preventing the scenario altogether by holding the line at Suwałki in the first place. Polish and Lithuanian troops train to fight there literally from Day One of any conflict, aiming to bottle up any incursion. Their doctrine calls for rapid defensive measures: blowing bridges, cratering roads, and leveraging every natural barrier. One Polish officer quipped that their job is “to make the Suwałki Gap as impassable as possible – a place where Russian tanks go to die.” The nature of the terrain supports this strategy, but success would depend on reacting fast and with sufficient forces.

It’s also worth noting that any attempt to close the Suwałki Gap inevitably involves Belarus. Geography dictates that Russia alone (from Kaliningrad) could not physically encircle the corridor without cooperation or involvement from Belarus to the south. An attack here would almost certainly mean an attack launched through Belarus or at least with Belarusian territory as part of the pincer. This raises the stakes significantly: it would turn any local skirmish into a multi-front war, directly implicating Minsk in aggression against NATO. For Moscow, that could be a complicating factor. While Belarus’ leader Alexander Lukashenko is aligned with the Kremlin, even he must weigh the risks of full participation in a war with the West. Some analysts believe Russia would hesitate to act in Suwałki without absolute certainty of Belarus’s support – otherwise a gap might remain on the Belarus side that NATO could exploit. In any case, the involvement of Belarus would broaden the conflict, likely prompting NATO to consider strikes against military targets inside Belarus or even Kaliningrad itself in retaliation. This prospect serves as a deterrent: all sides understand that the Suwałki Gap, though a tiny area, could trigger a much larger conflagration.

Recent Developments: Bolstering the Baltic Flank

Russia’s war against Ukraine since 2022 has transformed the security calculus in Northern Europe. For the countries of the Nordic-Baltic region, it was a wake-up call that the Kremlin’s aggressive ambitions are very real – but it also bought them time as Russia’s forces became tied down to the south. In response, NATO has moved from tripwire deterrence to forward defense in the Baltics. In practical terms, this means beefing up NATO’s military presence and preparedness around the Suwałki Gap and the broader region. In the years after 2014, NATO deployed multinational battlegroups to each Baltic state and Poland as an “Enhanced Forward Presence.” These were relatively small battalions (around 1,000 troops each) intended as a symbolic tripwire. However, after the Ukraine invasion, NATO leaders agreed that symbolism is not enough – any Russian attack must be met by a force that can actually fight and deny a quick victory. At the NATO Madrid Summit in 2022, and reaffirmed in Vilnius in 2023, the alliance decided to scale up those battlegroups to brigade-sized units (roughly 3,000–5,000 troops each). Germany, for instance, has committed to lead a full brigade in Lithuania, building on its existing battlegroup there. Canada, which leads the NATO unit in Latvia, has likewise announced plans to reinforce it towards brigade strength, with additional contributions from countries like Spain and Italy. The United Kingdom leads the battlegroup in Estonia, and the United States rotates troops through Poland and the Baltic states as well. These moves are about sending a clear message: NATO is serious about defending every inch of Baltic soil, and any aggressor will face a multinational wall of forces from day one.

.jpg)

One of the most significant shifts has been the historic decision of Finland and Sweden to join NATO. Finland became a NATO member in April 2023, and Sweden is expected to follow suit soon (as of early 2026). The inclusion of these two Nordic nations fundamentally redraws the strategic map of the region. Suddenly, the Baltic Sea is almost entirely encircled by NATO territory – from Norway’s North Cape all the way around to Germany. “NATO can now operate across land, sea, and air [in Northern Europe]. The Suwałki Gap – once a narrow lifeline – is now one of several reinforcement routes,” noted a policy brief by the Center for European Policy Analysis. Indeed, Finnish territory provides alternative pathways to the Baltics: for example, in a crisis NATO could send reinforcements through northern Finland to Estonia via the Baltic Sea, or even overland from Norway/Sweden into Finland and then by sea to the Baltics. Additionally, Sweden’s Gotland Island in the middle of the Baltic Sea gives NATO a forward position to monitor and control maritime access. These developments diminish the sense of total dependence on the Suwałki corridor that existed before. As one expert put it, NATO’s Baltic flank is no longer a tiny cul-de-sac but part of a broader Nordic-Baltic defense zone. This has led some to argue that the Suwałki Gap is now less of an inviting target for Russia than it was in the past, since NATO has more ways to respond and reinforce (the “threat is now smaller than ever,” as one headline in 2023 optimistically put it).

However, new opportunities come with new complexities. With Finland and Sweden in the fold, NATO’s defensive line is longer and touches previously neutral frontiers. The alliance must coordinate across a larger expanse – from the Arctic down to the Suwałki Gap – and ensure troops can move rapidly to where they’re needed. The Baltic Sea, now largely a “NATO lake,” still has to be secured against Russia’s naval and air capabilities. And critically, Kaliningrad does not disappear as a threat. In fact, some military planners worry that as NATO fortifies the mainland Baltics, Russia might lean even more on Kaliningrad’s arsenal (such as deploying more Iskander ballistic missiles there) to intimidate or blockade the corridor in a crisis. The region is now bristling with activity: NATO conducts frequent military exercises in the Baltics and Poland, and Russia conducts large drills, like the periodic Zapad war games, that practice closing the Suwałki Gap from the Russian side. In 2023, an unexpected twist added to tensions – the presence of the Wagner Group mercenaries in Belarus. After the Wagner private army’s mutiny in Russia, hundreds of its fighters relocated to Belarus, and by mid-2023 there were reports of Wagner mercenaries training Belarusian troops just across from the Suwałki sector. Poland and Lithuania reacted warily, beefing up border security and deploying additional troops near the gap, unsure of what these unpredictable fighters might do. Fortunately, the Wagner threat dissipated within a couple of months; by late 2023 the mercenaries had left Belarus following the group’s disbandment after Yevgeny Prigozhin’s demise. This episode, albeit brief, was a vivid reminder of how quickly the Suwałki region could become a flashpoint. It prompted the Polish and Lithuanian publics to pay even closer attention to their countries’ defense readiness.

On the brighter side, regional cooperation to secure the Suwałki Gap has intensified. Poland and Lithuania have formed a joint military council and even affiliated specific army units to train together for the gap’s defense. The Lithuanian “Iron Wolf” Mechanized Brigade now regularly drills with Poland’s 15th Mechanized Brigade, learning to “fight as one” in this area. Such efforts recall a bit of medieval history – some in Warsaw and Vilnius liken it to the two nations banding together as they did in the 15th century Battle of Grunwald, this time to face a threat from the East. Moreover, the broader Nordic-Baltic community is coordinating like never before. Under the auspices of initiatives like NORDEFCO (Nordic Defense Cooperation) and the UK-led Joint Expeditionary Force, Nordic and Baltic militaries are sharing intelligence, conducting joint exercises, and aligning their contingency plans. The presence of Canadian, German, British, and other NATO troops on rotation in the region also provides valuable integration – for instance, a Canadian-led NATO brigade in Latvia (with troops from several nations) means North American and European soldiers are gaining on-the-ground experience in Baltic terrain and working together with local forces. All of this boosts deterrence: the more knit-together and prepared NATO is here, the less likely Russia is to test it.

Finally, the European Union is playing a supporting role. While NATO is the primary military guarantor, the EU has tools that matter for resilience – especially infrastructure and economic measures. The EU’s funding of the Rail Baltica project is one example: a high-speed rail line under construction will connect Poland with Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia (and link up to Finland via ferry). Once completed, Rail Baltica will provide a modern transport corridor through the Suwałki region, not only boosting commerce but also enabling faster movement of NATO troops and equipment to the Baltics if needed. Additionally, EU initiatives are underway to improve roads, bridges and fuel pipelines in Eastern Europe, explicitly to meet what’s called “Military Mobility” standards for rapid reinforcement. The logic is simple: in a crisis, NATO reinforcements might have to race hundreds of miles across Europe to reach the fight – and any bottleneck (be it bureaucratic border crossings or literal bridge weight limits) could cost precious time. The Suwałki Gap, being a narrow passage, would be the last place you want a traffic jam when tanks are needed at the front. Recognizing this, EU and NATO planners have coordinated on removing legal and logistical hurdles so that, for example, a German armored brigade can roll through Poland and Lithuania at short notice. In sum, recent years have seen a flurry of activity to strengthen the Baltic region’s defenses and mitigate the once-dire vulnerabilities of the Suwałki Gap. As a result, many analysts now consider NATO’s northeastern flank far more robust than it was a decade ago. “The Nordic-Baltic region is no longer NATO’s weak point. It’s becoming one of its most resilient areas,” writes one Lithuanian security expert. But new strength does not equal invincibility – vigilance remains the watchword.

Humanitarian Stakes and Transatlantic Solidarity

Discussions of the Suwałki Gap often sound abstract and highly technical – all about troop movements, tank weights, and battle plans. It is crucial to remember that real lives and communities are at the heart of this issue. For the people of Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia (as well as Poland), the security of the Suwałki corridor isn’t an academic topic – it could determine their very fate in a war. These nations are not simply “strategic pieces” on a chessboard; they are home to millions of individuals who have built thriving democratic societies since the end of Soviet occupation. A conflict that isolated the Baltic states would put those people in grave danger. We have only to look at the humanitarian horror unfolding in Ukraine since 2022 to imagine what war in the Baltics might entail: mass displacement of families, cities under bombardment, refugees streaming westward, and the risk of atrocities under an occupying force. It is no exaggeration to say that preventing a war in the Suwałki Gap is a humanitarian imperative for Europe. The Baltic diaspora communities in North America know this well – many Lithuanian, Latvian, and Estonian families in the US and Canada have parents or grandparents who fled war and repression in the 20th century. They fervently wish never to see such trauma visited upon their homelands again.

In the border towns near the Suwałki Gap, daily life goes on peacefully at present. Farmers till their fields, children attend school, and cross-border trade flows with little fanfare. Local residents, whether Polish or Lithuanian, are of course aware that one of the world’s tensest geopolitical fault lines runs through their backyard, but they refuse to live in constant fear. They have confidence that NATO’s presence – including American, Canadian, and European troops training nearby – acts as a strong deterrent to any would-be aggressor. Over the past few years, civil defense preparations have also been revived in the Baltic region as a prudent precaution. Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia have reintroduced conscription and are investing heavily in civil resilience measures. This means more training for reservists, new volunteer home guard units, stockpiling of emergency supplies, and even building or refurbishing bomb shelters. The goal is to ensure that if the worst ever happened, communities could hold together and survive until help arrived. In Estonia, for example, the population regularly practices large-scale evacuation drills and mobilization exercises – a stark reflection of lessons learned from Ukraine’s experience. While nobody in the Baltics wants war, they are determined to be prepared for anything, hoping that preparedness itself will deter an attack.

Transatlantic unity remains a linchpin of preventing conflict over the Suwałki Gap. The United States and Canada, as NATO allies with significant Baltic and Nordic diaspora populations, have a deep stake in this region’s peace. Canadian troops in Latvia and American battalions rotating in Poland and Lithuania are more than just soldiers – they are also seen as symbolic protectors of shared values and people-to-people ties. When North American NATO troops train in the Baltics, often there are local Latvian or Lithuanian-Americans in their ranks, proudly defending the soil of their ancestors. This intertwining of communities reinforces the political will on both sides of the Atlantic to stand firm against Russian aggression. U.S. congressional delegations frequently visit the Suwałki area and Baltic capitals, sending messages of support. Likewise, Baltic leaders make a point of engaging with diaspora groups during visits to North America, thanking them for advocating Baltic security interests in Washington and Ottawa. Such engagement has paid off: despite occasional isolationist rhetoric, the mainstream view in the U.S. and Canada remains strongly committed to NATO’s Article 5 guarantees for Baltic allies. The humanitarian argument – that we must not allow free nations to be swallowed by an authoritarian neighbor – resonates strongly in Western public opinion, especially after witnessing Ukraine’s suffering. In short, solidarity is not just a slogan; it’s a strategy to ensure any threat to the Suwałki Gap and the Baltics is met with unified resolve.

Looking Ahead: Ensuring the Gap Remains Just a Gap

As of early 2026, the Suwałki Gap is peaceful and still firmly under NATO control – and everyone intends to keep it that way. Military planners often say the gap is a strategic problem that has no perfect solution, only constant management. That management involves continued investment in defense, joint exercises, intelligence-sharing, and yes, diplomacy. It means communicating to Moscow that NATO’s red lines are unambiguous, while also avoiding unnecessary provocation that could spark a crisis. It means working with Belarus (to the extent possible) to prevent incidents or miscalculations along that border, even as Minsk remains aligned with Russia. And it means keeping the people who live in this region resilient and informed, so that misinformation or panic cannot take hold.

The coming years will likely see further steps to harden the Suwałki corridor’s security. Already, experts call for upgrading local infrastructure – for example, strengthening bridges and highways to handle NATO heavy armor and improving rail links. More permanently stationing allied troops in the region is another frequently raised idea (Poland has even offered to host a U.S. base – sometimes nicknamed “Fort Trump” in reference to an earlier proposal). Additionally, modern early-warning systems are being installed to monitor movements in Kaliningrad and Belarus, so NATO isn’t caught by surprise. The Baltic states themselves continue to procure new defensive weapons, from anti-tank missiles to air-defense systems, to make any potential invasion as difficult as possible. All these efforts boil down to a simple principle: deter aggression by making it likely to fail. The Suwałki Gap may be narrow, but if it is well-defended and NATO is ready to respond, then attempting to storm through it would be a fool’s errand.

In the end, optimism is cautiously returning to the Nordic-Baltic region. What was once seen as NATO’s most vulnerable flank is now becoming a strong, unified front. The addition of Finland and Sweden has brought powerful new militaries into the mix, and the commitment of allies like the U.S., Canada, Germany, and the UK remains solid. The Suwałki Gap will likely always be a point of strategic concern – geography isn’t something one can change – but it no longer feels like a gaping wound waiting to happen. As one Lithuanian official remarked, “We’ve turned the Suwałki Gap from a symbol of weakness into a showcase of our resolve.”

For the people of the Baltic states and their friends abroad, that resolve is ultimately about protecting the peace and freedom that were so hard-earned after the Cold War. Ensuring the Suwałki Gap remains open and secure is part of ensuring that the Baltic nations can continue to thrive in safety. Every year without conflict is a victory for the ordinary families living in Kaunas, Daugavpils, or Tallinn – families who, like any others, simply want to raise their children without the shadow of war. The humanitarian stakes could not be higher: if deterrence fails here, the human cost would be enormous. Thankfully, NATO, the EU, and the Nordic-Baltic countries are working tirelessly to prevent that nightmare scenario.

.svg)

In the words of a Latvian defense official, “The Suwałki Gap is a test of our unity. If we stand together, it will remain what it is – just a quiet borderland. But if we waver, it could become a flashpoint with global consequences.” For now, all signs indicate that the transatlantic community understands this. The Suwałki Gap, once seen as a fatal weak link, has galvanized NATO to show its strength. As long as that unity holds, the narrow corridor will stay firmly in the hands of peace – a gap that, with hope and effort, no adversary will ever close.

.png)

.png)

.png)