The front arch – a steel parabola 73 m across and 32 m high – leans over the stage, supporting a suspended roof of timber and a 3×3 m grid of steel cables. This innovative design created a self-supporting acoustic shell that could shelter an astonishing 15,000 singers on tiered choir stands. At the time of its construction, such a large-scale thin-shell roof was cutting-edge, signaling a return of modernist architecture during the Khrushchev Thaw.

Western Inspiration and Design Challenges: The Tallinn arch’s dramatic form drew inspiration from Western open-air amphitheaters and band shells that the architects had seen in magazines. Tourists often compare it to an oversized Hollywood Bowl – the famous outdoor music shell in Los Angeles – albeit on a much grander scale. Like those Western precedents, Tallinn’s arch was meant to naturally amplify sound for crowds of tens of thousands without electronic aid. However, building such a structure under Soviet conditions posed challenges. The engineering had to be calculated by hand – no computers – and materials like high-strength concrete and steel cables were scarce. Kotli enlisted talented collaborators: structural engineer Endel Paalmann to oversee construction, and acoustics expert Helmut Oruvee to fine-tune the sound. The result was impressive but not acoustically perfect. Professor Jüri Lavrentjev, an acoustician at TalTech, explained in an ERR Radio interview that the arch was a compromise between beauty and function – it does reflect the choir’s sound toward the audience, “only not quite as well as perhaps it could,” because the singers stand relatively far from the arch.

In essence, the giant shell gives some boost to the collective voice and shields performers from wind and rain, but direct sound still dominates in the audience. Despite these quirks, the singing arch became a beloved national symbol. In 1988 it famously hosted the Singing Revolution gatherings, when over 100,000 Estonians filled the grounds to sing for freedom. The very presence of this modern arch – built to celebrate Soviet Estonia’s 20th anniversary in 1960 – ironically helped preserve the Estonian identity and choral tradition through the Soviet era.

Lithuania’s Identical Twin: Vilnius’ Vingis Park Song Stage

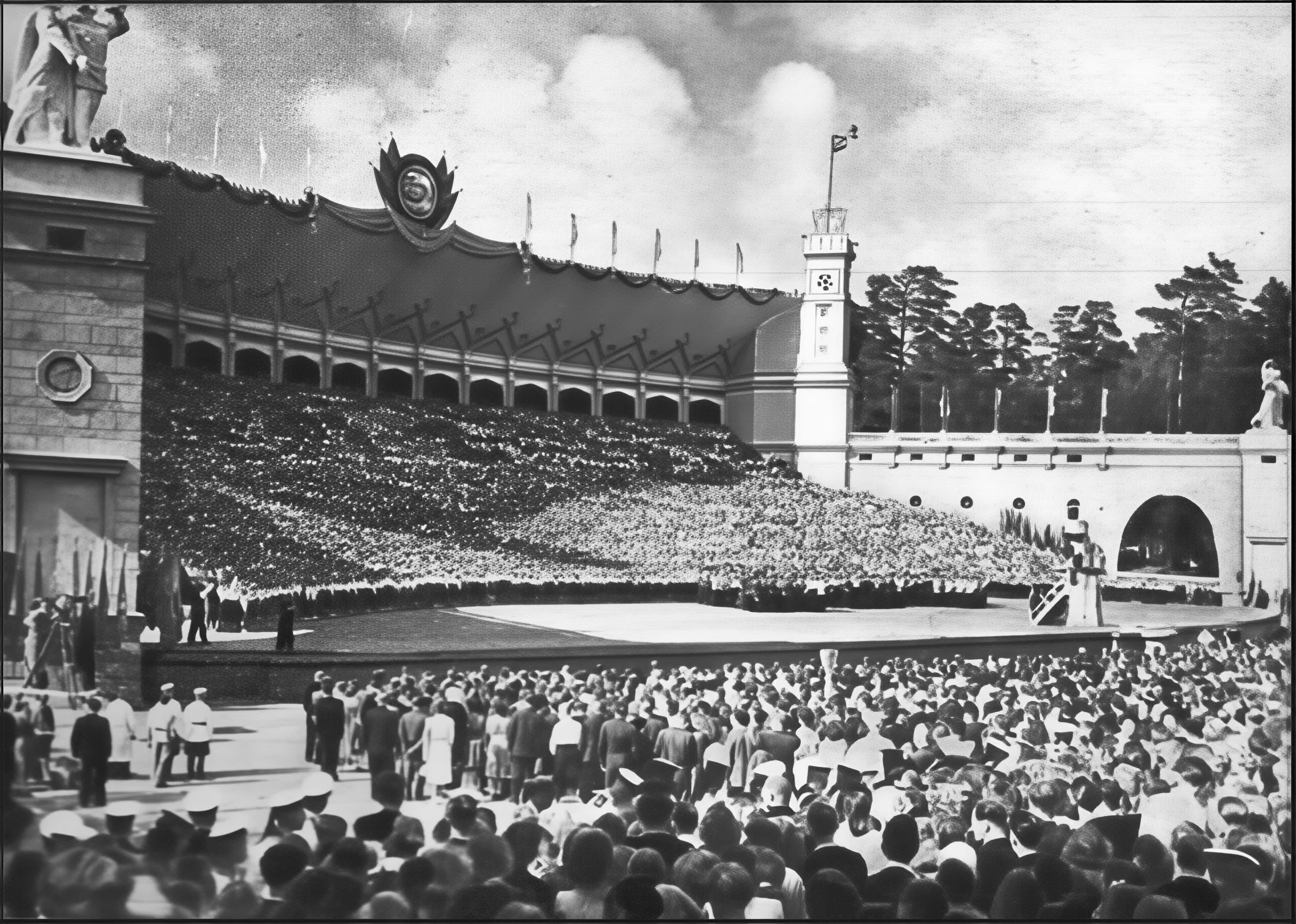

Just a few years after Tallinn’s arch rose, Lithuania got a twin. In July 1960, the Vingis Park amphitheater in Vilnius opened for the Lithuanian Song Celebration, and it looked strikingly familiar. In fact, the Vilnius stage was based on a modified design of the Tallinn Song Festival Grounds. It features the same signature curved shell canopy and arching profile. Archival sources show that the Soviet authorities essentially replicated the Estonian design for Lithuania – even the Estonian architects Kotli and Sepmann were credited as co-designers of the Vilnius stage. The result was a nearly identical open-air song stage, complete with a sweeping arch and tiered choir risers. Vilnius’ version was slightly scaled to fit its park setting, accommodating around 12,000 singers instead of 15,000. The family resemblance is undeniable: both structures are grand, white concrete shells hugging a semicircular choir stand, open to a grassy spectator field. To this day, an onlooker could easily mistake a photo of an empty Vingis Park stage for Tallinn’s, if not for the Vilnius TV Tower rising in the background (which actually adds to the déjà vu, as Tallinn’s arch also has a tall flame tower beside it!).

.avif)

Why copy the Estonian blueprint? At the end of the 1950s, both Estonia and Lithuania were part of the USSR and preparing for major song festivals. The success of Tallinn’s modern arch likely caught Moscow’s attention as a showcase project that could be reproduced. Lithuania’s Song Festival was gaining popularity, and the authorities approved building a similarly monumental stage in Vilnius to elevate the event’s grandeur. By 1960, Vilnius had an ultra-modern Song Festival Grounds of its own, giving physical form to a tradition that, in Lithuania’s case, was approaching its 40th anniversary. The arch quickly became central to Lithuania’s song celebrations and national pride, just as in Estonia. A fun fact noted by cultural historians: both the Tallinn and Vilnius song-stage arches trace their conceptual roots back to Western examples of acoustic shells, but they ended up as unique Soviet-Baltic hybrids – locally built, immense in scale, and used for patriotic mass singing rather than orchestra concerts. Over time the Vilnius stage has hosted not only folk song festivals but also pop concerts (it famously held a 60,000-strong crowd at a rock concert in 1997), proving the versatility of the design. Today, as Lithuania celebrates over 100 years of its Song Festival tradition, the Vingis Park arch remains an iconic venue – literally a sister structure to Tallinn’s beloved Laululava.

Latvia’s Different Tune: Mežaparks and a Modern Reinvention

What about Latvia, the middle Baltic nation? It turns out Latvia did not follow the same architectural script during the Soviet era. Instead of copying the Tallinn arch in the 1960s, Latvia stuck with its own solution. The Latvian Song and Dance Festival (as it includes dance) moved to a new open-air stage at Mežaparks in Riga in 1955, a few years before Estonia and Lithuania built their shells. The Mežaparks Great Bandstand of 1955 was designed by architect Vladimir Šnitnikov in a more conventional style – essentially a broad, open stage with wooden choir stands and no dramatic concrete arch. It could fit about 10,000 singers and had bench seating for 30,000 spectators, plenty for the time. Because this facility was relatively new and functional, Latvia’s Soviet authorities saw little need to rebuild it in 1960. Thus, Latvia never got a Tallinn-style arch in the Soviet decades. The Mežaparks stage became an icon in its own right, hosting massive song festivals (200,000 people famously attended in 1988 during Latvia’s Singing Revolution) even without a shell roof. Over the years, Latvians came to cherish their unique venue – an open “choir garden” surrounded by pines, symbolizing their own path.

Fast forward to the 21st century, and Latvia decided to do something bold. Rather than replicating the old Soviet-era designs, Riga held an international competition to reconstruct the Mežaparks stage for a new era. The result, completed in phases by 2021, is a strikingly modern amphitheater that some call an “artificial forest” for song. The new design by architects Austris Mailītis and Juris Poga features a sweeping curved roof with hundreds of suspended acoustic panels, evocative of leaves or a forest canopy, above expanded choir stands for nearly 14,000 singers. This high-tech structure (nicknamed the Silver Grove for its silvery lattice) is tuned to enhance sound across an audience of 60,000, all while blending into the surrounding woodland. In 2021 it won Latvia’s Architecture Grand Prix for how elegantly it “resonates with its forested surroundings” and honors the tradition. In essence, Latvia has forged its own architectural identity for the Song Festival – one that suits its needs and landscape, rather than borrowing from its neighbors.

Despite these divergent paths, all three Baltic nations remain united by the Song Festival tradition itself – a UNESCO-listed cultural heritage. Whether under Estonia’s and Lithuania’s twin mid-century arches or Latvia’s revamped Mežaparks stage, the core idea is the same: tens of thousands of voices singing in unison, supported by architecture that amplifies the power and joy of communal song. Each stage, in its own way, is a monument to the “singing nations” of the Baltics.

Final Thoughts

It is fascinating how architecture and music intertwined in the Baltics. The Estonian and Lithuanian stages show a rare case of “copy-paste” design in Soviet architecture – a successful idea in one republic literally echoed in another. Meanwhile, Latvia’s route reminds us that there is more than one way to build a stage for 20,000 voices. From Tallinn’s pioneering singing arch to Vilnius’ echoing twin, and now Riga’s forest-inspired arena, each solution reflects a blend of practicality, politics, and national character. What unites them is the purpose: to give form to a cultural phenomenon – thousands singing as one – that defines these nations. In the Northern European sky, these three open-air stages continue to stand as grand architectural accompaniments to the soaring northern voices they help project.

.png)

.png)

.png)