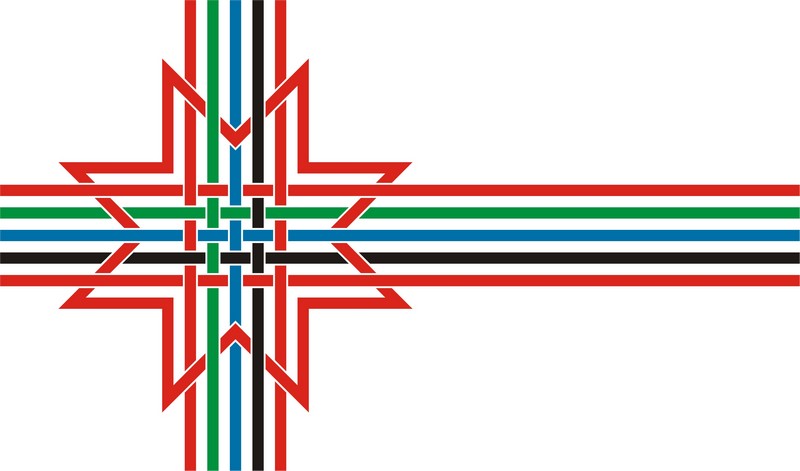

On a typical culture night in Tartu or Turku you’ll see the familiar blues and whites, tricolors and county pennants. Every so often, though, a different cloth appears: a white field with an offset cross, color bars that hint at Estonia and Hungary, and a small red eight-pointed rosette at the center. It’s not a state flag. It was never adopted by any congress. Yet the proposed Finno-Ugric (Uralic) flag has quietly threaded itself into festivals, student clubs, and diaspora feeds for more than a decade. Designed by Polish Finno-Ugric linguist Szymon Pawlas, it was published for public use with a simple promise: here is a family banner—if it speaks to you, fly it.

The internet made it; tradition explains it

The project’s website introduces the flag as the “official website of a proposed flag for Finno-Ugric (Uralic) peoples,” and it does something unusual for vexillology: it invites everyone to download the artwork in multiple formats—“feel free to use the flag wherever you want to promote Finno-Ugric interests.” That “commons first” stance helped the design circulate far beyond any single institution.

Look closer and the design reads like a miniature atlas. The cross layout nods to the Nordic visual language familiar on Finland’s flag. The palette plaits together cues many viewers recognise immediately—Estonia’s blue-black-white and Hungary’s red-white-green. At the center sits a red eight-pointed rosette, the same solar sign that appears on the flag of Udmurtia, where it is described officially as a protective symbol of the sun and life. In the project’s own words, the flag is “quite colourful,” intended to symbolize the diversity of Finno-Ugric peoples, held together on a white ground.

A long shadow: Pan-Finnicism’s complicated legacy

To understand why a pan-family banner appeals at all, it helps to revisit the early 20th-century idea of Pan-Finnicism—a broad, sometimes romantic, sometimes political push to imagine closer ties among the Finno-Ugric peoples. In its more ambitious moments it intersected with the “Greater Finland” current; in its cultural form it was simply a call to recognise kindred languages and histories across borders. After the Second World War—and especially under Soviet dominance—the political strands of Pan-Finnicism largely faded from view. The cultural kinship never disappeared, but the grand unification rhetoric went out of fashion.

That history matters for a flag trying to speak to many communities at once. A pan-banner can be read as inclusive shorthand—or as a relic of old projects that some remember uneasily. The designers leaned into the former: a community emblem for festivals and classrooms, not a polemic.

Why it never became “the” flag

No single constituency. Even the label is tricky. “Finno-Ugric” is a disputed subdivision inside the broader Uralic family; many scholars prefer “Uralic” as the umbrella, which raises a basic question: who exactly is this flag for? That ambiguity alone chills formal adoption.

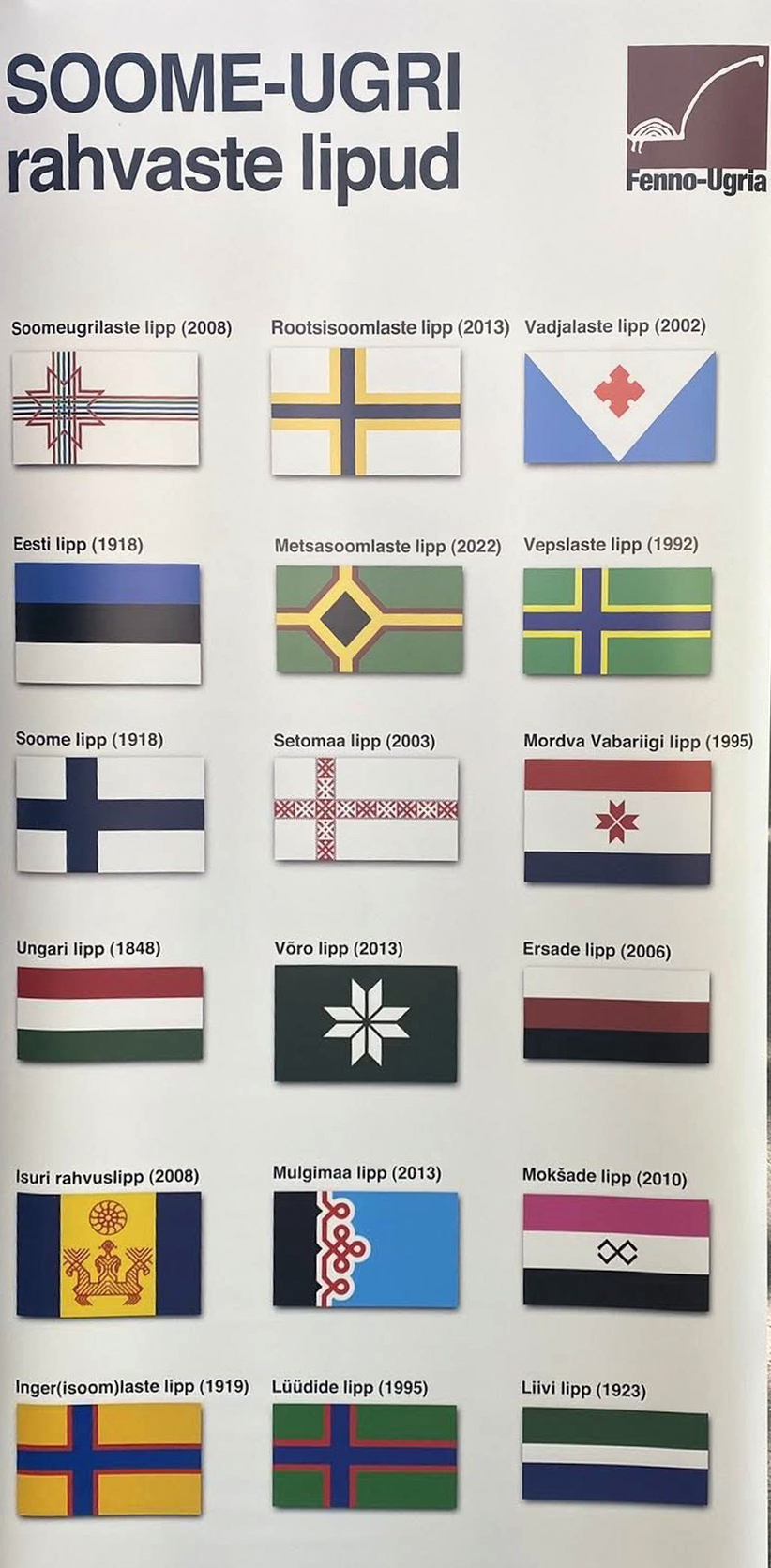

Strong local symbols. Sámi communities have their own widely recognized flag; Udmurtia, Mordovia, Mari El and others have official republican flags; Estonia, Finland and Hungary have powerful national brands. A composite pan-flag naturally competes with identities people already carry. (The Udmurt rosette, for instance, is cherished precisely because it is local and official.)

Politics at the edges. Large parts of the Finno-Ugric world live as minorities inside the Russian Federation; trans-border symbols can be sensitive. The project kept itself intentionally grassroots and apolitical, which helps visibility but limits institutional uptake.

It was designed to be shared, not owned. By releasing free downloads and encouraging community use, the flag spread widely—but it also stayed outside the structures that normally legitimize symbols (laws, resolutions, charters).

And yet, it keeps finding an audience—especially in Finland and Estonia

What keeps the banner alive is precisely what made it possible: open circulation and a clear visual story. In Finland and Estonia—two modern states where Finnic languages and Nordic aesthetics overlap—the flag works as a shorthand for kinship without asking people to choose politics. You see it pop up in community pages and events, and in years when Finno-Ugric observances trend online, the same artwork resurfaces with attribution to Pawlas and links back to the project site. It’s not official—but it is legible, and that counts.

What a non-state flag can still do

Flags are tools as much as they are claims. This one doesn’t draw borders; it names a relationship—between languages, archives, families, choirs, research networks. When a teacher in Võru needs a single image to introduce Uralic cousins, when a Helsinki student group wants a banner that says our family is bigger than our passport, when an Estonian festival wants to salute kindred peoples without speaking for them—the file is there, and it's up to the people to use it and adopt it or not. Flags and symbols like any other that unite people and provide quick recognition and meaning when used in public.

And that might be the lesson. In a century wary of grand unifications, a shareable, optional flag can still do quiet cultural work: keeping the Finno-Ugric world in view, and giving all Finno-Ugric people—and everyone who cares about them—a compact way to say we remember our kin.

.png)

.png)

.png)