These nations speak languages that are “distinctly different from Indo-European languages that dominate much of Europe”, belonging instead to the Finno-Ugric branch of the broader Uralic language family. In a continent awash in Indo-European dialects, Finnish, Estonian, and Hungarian stand apart as linguistic islands, a curious legacy of ancient migrations and resilient cultures.

The Finno-Ugric Family Amid Indo-European Neighbors

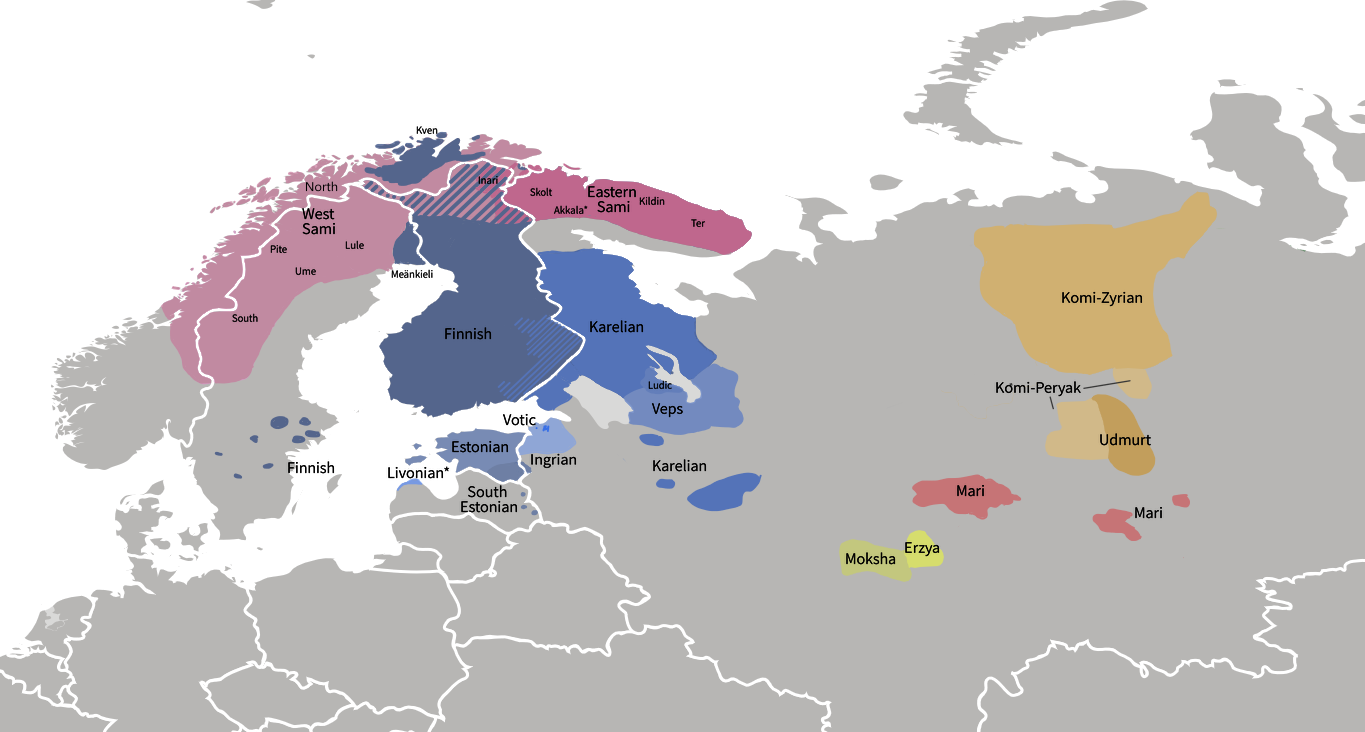

Estonia, Finland, and Hungary form a peculiar trio in Europe: each is bordered by Indo-European-speaking peoples, yet their national tongues share common Finno-Ugric roots with each other and with far-flung communities in the north and east. Uralic (Finno-Ugric) languages are spoken by roughly 25 million people scattered from northern Europe to Siberia. The largest among them are indeed Hungarian (about 12–15 million speakers), Finnish (~5 million), and Estonian (~1 million), which are unique in being the only Uralic languages that enjoy majority status and official national use. Most other Uralic tongues survive as minority languages in Russia and Scandinavia. For example, the indigenous Sámi (Lapp) languages persist in Arctic Lapland, and small Uralic languages like Mari, Komi, Udmurt, Erzya, Moksha, and others are spoken in pockets across the Volga and Ural regions – often as tiny ethnic enclaves with limited recognition.

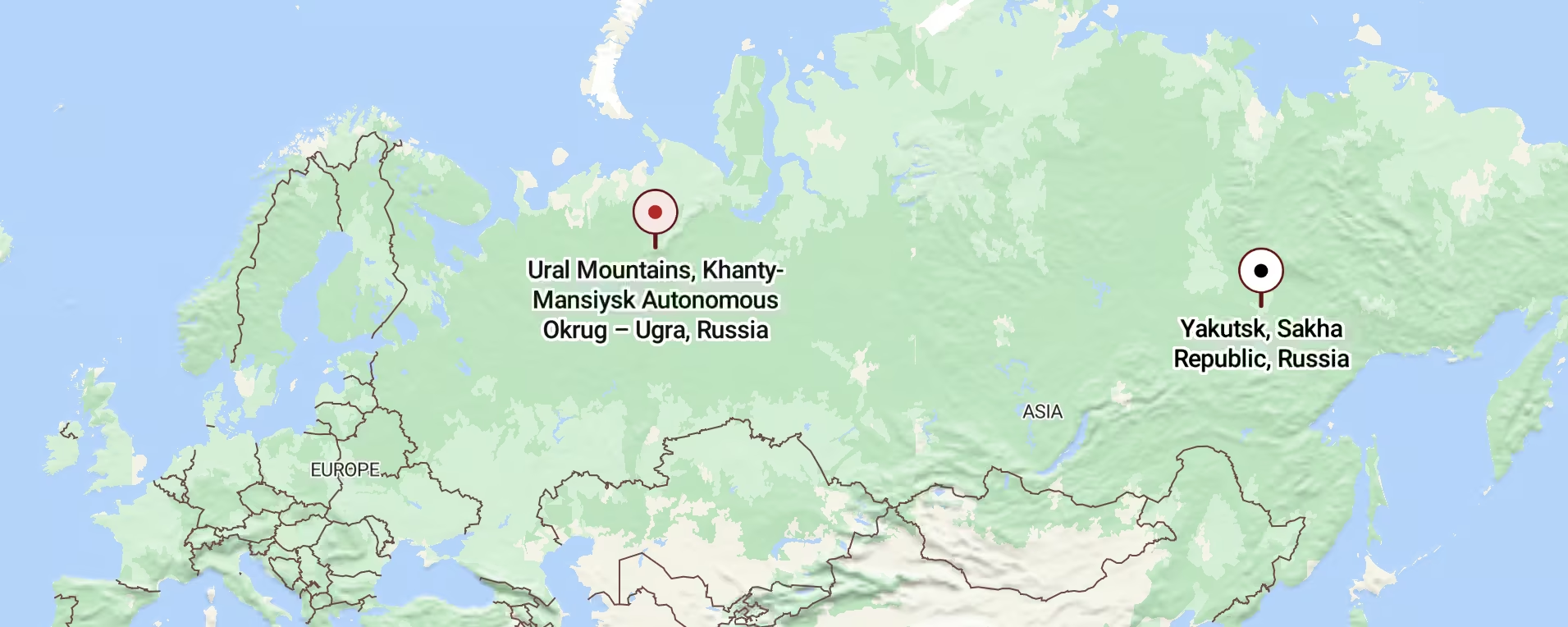

Crucially, what unites this far-flung family is not geography but linguistic kinship: a shared origin and structural similarity that set them apart from the Indo-European majority. The very term “Uralic” hints at an origin near the Ural Mountains, and indeed for much of the last two centuries scholars assumed that the proto-Uralic homeland lay in the forests around the Urals (the traditional gateway between Europe and Asia). The Finno-Ugric languages (a major subgroup of Uralic) were thus thought to have spread westward from the Urals long ago, explaining why we find Finnish on the shores of the Baltic and Hungarian in the Carpathian Basin. In contrast to their Germanic, Slavic, or Romance neighbors, these languages descend from an entirely different ancestral tongue and migrated along a very different route. As a result, Finns, Estonians, and Hungarians speak languages more closely related to each other – and to distant cousins in Siberia – than to the Indo-European tongues of their immediate neighbors. It’s a bit as if a small piece of Eurasia’s far north had broken off and drifted into Europe’s heart, linguistically speaking.

Uralic languages today occupy a vast crescent of territory “from Norway in the West and the Ob River region in the East, to the lower Danube in the South”. In other words, communities speaking Uralic tongues are strewn from Lapland and Finland across northern Russia (through Karelia, the Volga basin, and Siberia) all the way to the Yenisei and Ob rivers in central Russia. Hungary marks the far southwest of this domain, a lone outpost on the Danube. These pockets of Finno-Ugric speech are surrounded on all sides by Indo-European (Germanic, Slavic, Baltic, Romance) and also Turkic language populations, highlighting just how unique their presence is in Europe. In effect, Estonians, Finns, and Hungarians are inheritors of a linguistic lineage that largely bypassed the Indo-European sweep of history. Understanding why requires a journey deep into prehistory – following the echoes of Uralic languages back to their source.

Ancient Origins: From Siberian Forests to European Shores

The story of the Finno-Ugric languages begins long before there were nations called Finland, Estonia, or Hungary. Linguists reconstruct a common ancestor called Proto-Uralic, from which all Uralic languages descend. For years, debate raged over where and when Proto-Uralic was spoken. Traditional theories placed this ancestral language near the Ural Mountains (hence the name), perhaps around 2000–3000 BC, as a small community of forest dwellers who later spread west and east. However, new research is dramatically reshaping this origin story. A 2023 ancient DNA study led by Harvard and University of Texas scientists found that the Uralic language family likely “emerged over 4,000 years ago in Siberia, farther east than many thought”. By analyzing genomes from hundreds of prehistoric individuals, researchers identified an ancestral population in central and northeastern Siberia (around today’s Yakutia), dating to roughly 2500 BC (~4,500 years ago), as the source of the distinctive genetic and linguistic legacy found in Uralic-speaking peoples. In other words, the earliest Uralic speakers may have lived not near the Urals at all, but much deeper in Asia – closer to Alaska or Mongolia than to Helsinki.

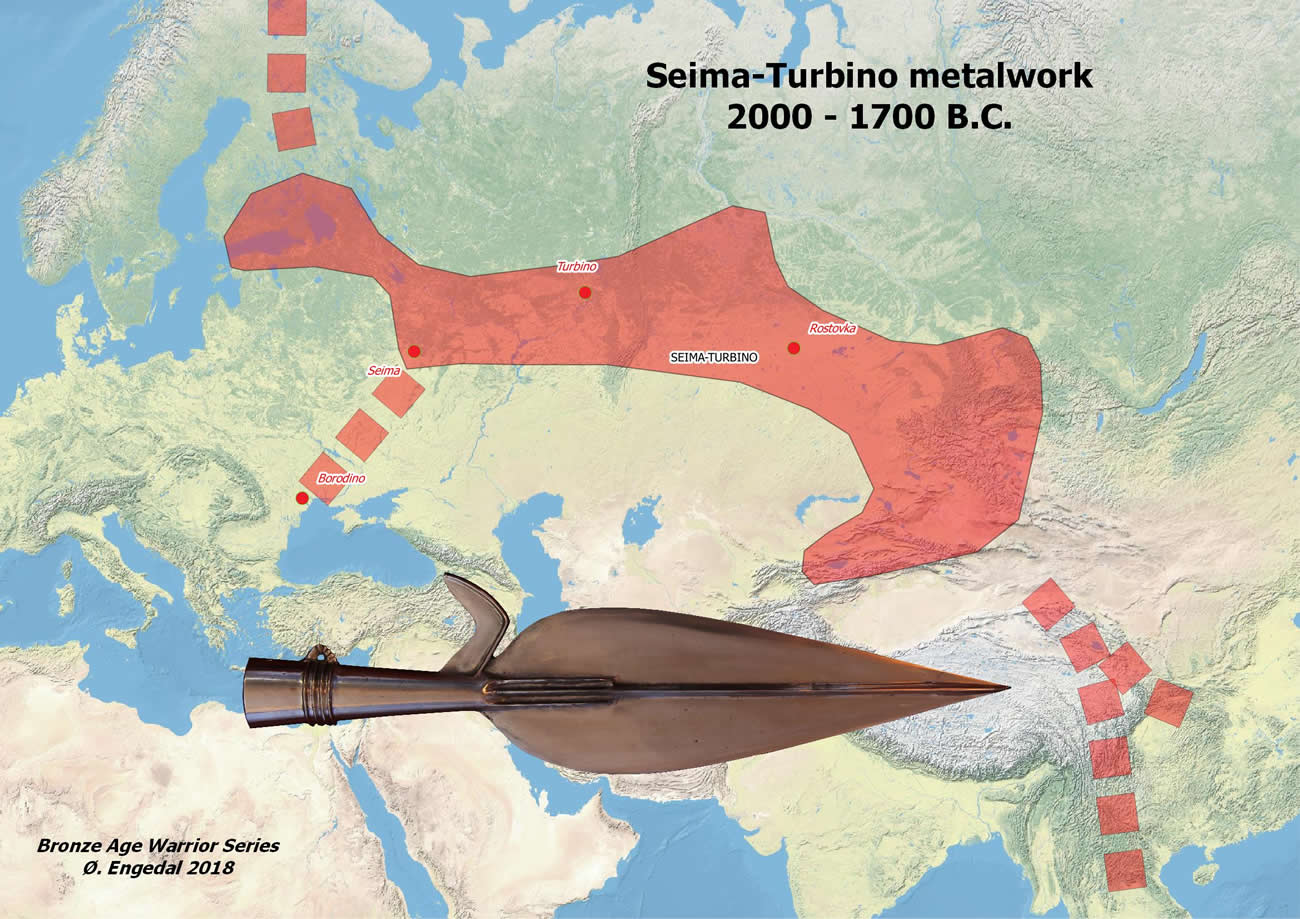

This finding gives new credence to a once-marginal theory that Uralic languages arose farther east, and helps explain some long-noted similarities with languages like Turkic and Mongolic (which might reflect ancient contacts in Siberia). From that Siberian homeland, the Proto-Uralic speakers expanded westward surprisingly quickly. Archaeology hints at a major population movement known as the Seima-Turbino phenomenon – a rapid dissemination of bronze tools, weapons, and perhaps people around 2000 BC across northern Eurasia. Intriguingly, scientists now suspect that Seima-Turbino’s vast trading network may have been the vehicle by which Uralic speech spread from Siberia into Europe. As bronze-age smiths and traders moved along the forested taiga belt, they likely carried their Uralic tongue with them.

Over the following millennia, branches of this Uralic family established themselves across the north. Some Finno-Ugric groups migrated to the Baltic Sea region in antiquity, giving rise to the early Finnic peoples – the ancestors of today’s Finns and Estonians. Others remained in the vast forests of Fenno-Scandinavia and European Russia (for example, the progenitors of the Sámi in Lapland and various Finno-Permic tribes around the Volga and Kama rivers).

Far to the southeast, a branch of Uralic known as Ugric took shape, which eventually produced the Magyars – the Hungarian people. The Magyar tribes originated east of the Urals and for a time dwelt in the Eurasian steppe, interacting with Turkic nomads, before sweeping into the Carpathian Basin in the 9th century AD and founding the Hungarian kingdom. To this day, Hungarian (Magyar) remains a “linguistic island” – a Uralic outlier in the heart of Europe, surrounded by Slavic, Germanic, and Romance languages.

Exactly how far into Europe Uralic languages reached in prehistory remains a topic of speculation. Some scholars have proposed that Finno-Ugric speech might once have been prevalent in Eastern and Central Europe before the spread of Indo-European tribes during the Great Migration period. This hypothesis posits that as Indo-European (IE) peoples – Celts, Germanic tribes, Slavs, etc. – expanded, they gradually displaced or assimilated earlier Finno-Ugric populations, leaving only the northern and eastern fringes (and Hungary) as remnants. While this view is not universally accepted, it underscores a tantalizing idea: the Finno-Ugric presence in Europe is ancient, possibly paralleling or even predating the influx of Indo-European languages. What is clearer from genetics and linguistics is that Uralic-speaking peoples moved “as far west as the Baltic Sea” over thousands of years, largely through the forest zone of Eurasia. Unlike the Indo-European expansion, which rode on horseback across steppes and plains, the Uralic expansion crept through bogs, rivers, and boreal woods – perhaps slower, but tenacious. The northern forests (taiga) acted as the highway of Uralic migration, from Siberia to Finland, which may be one reason Uralic languages survived in the north while Indo-European swept through more open lands to the south.

Unmistakably Different: Uralic vs. Indo-European Languages

Having originated separately for thousands of years, the Uralic (Finno-Ugric) languages evolved features quite unlike those of their Indo-European neighbors. To the layperson, the difference is apparent at a glance: a Finnish or Hungarian sentence looks long and complex, packed with unfamiliar letter combinations, where a similar sentence in English or French might be much shorter. These contrasts spring from deep structural differences:

- Agglutinative Grammar: Finno-Ugric languages are highly agglutinative, meaning they string together many suffixes (and sometimes prefixes) onto a word root to express grammatical meanings. Instead of using separate prepositions or auxiliary words, a single Finnish or Hungarian word can carry a bundle of information. For example, in Finnish talossanikinko means “in my house, too,” with multiple suffixes (-ssa in, -ni my, -kin also, -ko question) glommed onto talo (“house”). This creates famously long words but also a precise, compact encoding of meaning. Indo-European languages, in comparison, tend to use more separate words or fused inflections rather than long agglutinative chains.

- Vowel Harmony: A hallmark of Uralic tongues is vowel harmony – a phonological rule that vowels within a word must “harmonize” as either all front vowels or all back vowels. Hungarian, Finnish, and Estonian all enforce vowel harmony, which gives their words a mellifluous, rounded sound. For instance, Hungarian asztal (“table”) takes the suffix -ban (“in”) as asztalban, but kert (“garden”) takes -ben as kertben, because a is a back vowel while e is a front vowel – the suffix vowel changes to match the front/back quality. Such harmony is virtually absent in neighboring Indo-European languages, making it a clear differentiator.

- Rich Case Systems: Finno-Ugric languages use numerous grammatical cases to indicate relationships that English might handle with prepositions. Finnish has around 15 cases, Estonian - 14, and Hungarian up to 18 distinct noun cases. These cases cover meanings like “into”, “out of”, “through”, “along with”, etc., all expressed by altering the noun’s ending. For example, where English uses prepositions (“in the house”, “from the house”, “to the house”), Finnish uses talossa, talosta, taloon respectively, modifying the root talo “house”. Indo-European languages like French or Spanish have lost most case-marking, and even Slavic languages (which have at most 7 cases) don’t approach the complexity of Finnish, Estonian or Hungarian’s case systems.

- No Grammatical Gender: In stark contrast to, say, German or Russian (where nouns can be masculine, feminine, neuter), Uralic languages do not assign gender to nouns or pronouns. There are no gendered articles or suffixes – a person is just “he/she” (hän in Finnish, which covers both genders). This lack of grammatical gender not only simplifies certain aspects of grammar (no need to make adjectives agree in gender, for example) but also stands out to European ears, since almost all Indo-European languages have gendered nouns or pronouns. Finnish or Estonian speakers learning German often stumble over remembering arbitrary noun genders, a concept entirely foreign to their mother tongue.

- Postpositions Instead of Prepositions: Many Finno-Ugric languages tend to use postpositions (coming after the noun) rather than prepositions. In Estonian, for instance, maja ees means “in front of the house” (literally “house front”). This again ties into the agglutinative nature – often these postpositions merge with nouns as suffixes (one could even consider them cases in some instances). While Indo-European languages like English use prepositions (before the noun), Uralic tongues often attach the equivalent concept to the end of the noun.

- Unique Vocabulary: Naturally, the vocabulary of Finnish, Estonian, and Hungarian shares common roots with each other (and with distant relatives like the Sami or Ugric languages), but has no inherent relation to Indo-European vocabulary. A Hungarian can’t pick up cognates from a German sentence the way a Polish or Spanish person might, for example. Basic words like the numerals and family terms are entirely different. (Finnish yksi, kaksi, kolme for one, two, three bear no resemblance to uno, dos, tres or ein, zwei, drei; the word for “mother” is äiti in Finnish, ema in Estonian – unrelated to mater, madre, mother of Indo-European.) This makes learning these languages a special challenge for outsiders – there’s very little familiar foothold. It also means that within their own family, Finns and Hungarians can sometimes find intriguing distant cognates: e.g., the Estonian word sada (“hundred”) and Hungarian száz (“hundred”) share a Proto-Uralic origin, even though these two languages parted ways thousands of years ago. Such links are invisible to their Indo-European neighbors.

These features (among others, like complex verb conjugation patterns, lack of future tense in Finnish, etc.) give Finno-Ugric languages a reputation for being challenging but fascinating for linguists. They often seem “backwards” or highly intricate to speakers of more prevalent European tongues. Yet from the perspective of Uralic speakers, it is the Indo-European languages that are the odd ones – lacking vowel harmony, shedding agglutination, and obsessing over gender! Each system has its own logic and beauty. The key point is that the Finno-Ugric languages preserved a very old structural profile that likely characterized their proto-language, whereas Indo-European languages evolved along a separate trajectory. Contact over centuries did lead to some convergence – for example, Finnish and Estonian borrowed many terms from Germanic and Baltic neighbors, and Hungarian absorbed hundreds of loanwords from Turkic and Slavic sources during its migrations. But in their grammar and core identity, Finnish, Estonian, and Hungarian remained true to their Uralic roots.

Myths, Theories, and the Puzzle of Origins

The striking divergence of Finno-Ugric languages from the European mainstream has invited much speculation over the years. Before modern linguistics settled the question, a number of alternative theories and myths attempted to explain who these peoples were and where their languages came from. Even as early as the 18th century, scholars were astonished to discover, for example, that Hungarian and Finnish – separated by geography and seemingly everything else – shared distant linguistic affinities. In 1770, Hungarian scientist János Sajnovics famously demonstrated a systematic relationship between Hungarian and the Lapp (Sámi) language, kick-starting Finno-Ugric comparative linguistics. His findings initially met with disbelief, since Hungarian aristocrats of the time preferred to think of themselves as descended from Attila’s Huns or other glamorous ancient peoples, rather than obscure northern tribes. This foreshadowed the “Ugric–Turkic war” – a fiery 19th-century academic debate in Hungary. On one side, mainstream linguists argued that Hungarian was an Ugric (Finno-Ugric) language related to Finnish. On the other, some Hungarian scholars (and nationalists) insisted on a Turkic or Hunnic origin for Hungarian, citing similarities with Turkic languages and the large number of Turkic loanwords in Hungarian vocabulary. For a time, the idea of a mixed origin gained traction – that Hungarian might be a hybrid of Ugric and Turkic elements. However, by the late 19th century the evidence weighed clearly in favor of the Finno-Ugric theory, and today the consensus among linguists is that Hungarian is a bona fide Finno-Ugric language (with many loans from Turkic, but not genetically “Turkic” itself). The passionate debates themselves became part of Hungarian intellectual history, reflecting how entwined language and identity can be.

On a broader scale, scholars have also speculated about possible connections between the Uralic languages and other major language families. One long-standing but controversial hypothesis, called “Indo-Uralic,” proposes that the Indo-European and Uralic families might share a common very ancient ancestor. Advocates of this idea point to a handful of similar-looking pronouns and core vocabulary items and the fact that the Proto-Indo-European homeland (the Pontic steppe) was not far from regions where Uralic peoples later lived. Indeed, some prominent linguists over the years – from Holger Pedersen to Björn Collinder – have supported the possibility of an Indo-Uralic super-family. Most linguists, however, remain unconvinced, arguing that the resemblances are too few or can be explained by ancient contact rather than common origin. Recent studies have found no conclusive genetic link between the two families’ basic vocabularies. Thus, Indo-European and Uralic are generally considered independent families – any similarity may just be due to proximity and interaction in prehistoric Eurasia.

Another old idea was the “Ural–Altaic” hypothesis, which grouped Uralic languages with the Altaic languages (a proposed family that included Turkic, Mongolic, and Tungusic, and sometimes Korean and Japanese). This was popular in the 19th and early 20th centuries, since Uralic and Altaic languages do share typological features like agglutination and vowel harmony. For a while, many believed that Finnish, Hungarian, Turkish, Mongolian, etc., all sprang from one macro-family tree. However, modern linguistics has largely abandoned the Ural–Altaic concept. It’s now seen that those common features are likely due to areal influence and coincidence rather than true genetic inheritance – an insight backed by the lack of consistent cognate words across Uralic and Altaic tongues. As one survey puts it, the old idea of Ural-Altaic unity “receives little support today”. Altaic itself (the grouping of Turkic-Mongolic-Tungusic) is considered unproven by many linguists. Instead, the consensus is that any similarities between Uralic and, say, Turkic languages arose from millennia of contact on the Eurasian steppes, not because they descend from a single ancestor. (For example, Hungarian’s resemblance to Turkic is better explained by historical interactions with Turkic peoples – as reflected in hundreds of loanwords – rather than a primordial “Ural-Altaic” mother tongue.)

These speculative theories, from Indo-Uralic to Ural-Altaic, highlight both our desire to find hidden connections and the unique status of Uralic languages as a puzzle piece that doesn’t quite fit with those around it. To this day, research continues – not to collapse Finnish and Hungarian into the Indo-European fold (that ship has sailed), but to refine our understanding of Uralic’s own internal history and its early contacts. The latest genetic evidence pushing the Uralic homeland into Siberia is one example of how new methods can upend old assumptions. It reminds us that the Finno-Ugric story is dynamic, with some chapters still obscured in the mists of prehistory.

Identity and Legacy: Proud Languages in Modern Europe

For the people of Finland, Estonia, and Hungary, their languages are more than just communication tools – they are core to national identity and cultural memory. Each of these nations at times had to assert the worth of their mother tongue in the face of dominant neighbors. In the 19th century, as nationalism swept Europe, language revival and standardization movements in Finland and Estonia transformed those tongues from peasant vernaculars into modern literary languages. Finland, for instance, was long governed by Swedish and Russian elites, and the elevation of Finnish to an official language in the late 1800s was a seminal moment in asserting a Finnish national identity distinct from Sweden or Russia. Estonia similarly underwent a “national awakening” where Estonian language newspapers, poetry, and eventually a national epic (Kalevipoeg) bolstered the Estonian identity under Czarist Russian rule. For Hungary, the Hungarian language never went underground (the Kingdom of Hungary maintained Magyar as a high language for centuries), but in the Austro-Hungarian Empire there were struggles to keep Hungarian on equal footing with German. The Hungarian Revolution of 1848 and subsequent reforms were in part about securing the rights to use Hungarian in governance and education. Even today, Hungarians celebrate their language as a source of pride, cherishing its rich literary tradition and unique vocabulary that sets it apart from all other European languages.

Interestingly, the three Finno-Ugric nations recognize their special kinship. Despite the great distances – and the fact that a Finnish speaker cannot understand a Hungarian on the street – Finns, Estonians, and Hungarians often refer to one another as linguistic cousins. They cooperate on cultural and scholarly fronts to sustain their Finno-Ugric heritage. Since 1931, scholars of these languages have convened the International Congress for Finno-Ugric Studies regularly to share research. More popularly, Estonia, Finland, and Hungary even jointly celebrate a Pan-Finno-Ugric Day every October 17 to honor their shared linguistic roots.

The presidents and cultural ministers of these countries often make a point of referencing their “unique language” in speeches, framing it as a gift from ancient ancestors that must be preserved. In Estonia, former President Kersti Kaljulaid notably said that preserving the Estonian language (and by extension kindred Uralic languages) is “a matter of national survival” in the modern world.

At the same time, these Finno-Ugric peoples are fully integrated into the regions where they live. Finns and Estonians are culturally Nordic/Baltic, and Hungarians have been part of the Carpathian basin’s history for a millennium. Their languages absorbed loanwords and influences from neighbors – for example, modern Estonian and Finnish are full of Old Germanic and Baltic loanwords, and Hungarian’s vocabulary reflects centuries of contact with Turkic, Slavic, and Germanic tongues. Yet the resilience of the core language is remarkable. Through foreign rule and globalization, they held onto the words and grammar passed down from the distant Uralic past. In a way, speaking these languages today is a living connection to a migration story that began in the Stone Age.

Why, then, are these three languages so different from those of their neighbors? The simplest answer – and the theme running through their history – is that they descend from a different branch of the human language tree, one that took root in the icy forests of Eurasia and survived on Europe’s fringes. Through chance, migration, and the tenacity of their speakers, Finnish, Estonian, and Hungarian endured where other Uralic voices fell silent or merged into the Indo-European chorus. Their distinctness is a testament to Europe’s early diversity: a reminder that not all roads lead to Rome (linguistically speaking). From the reindeer herders in Lapland to the horsemen of the steppe, Finno-Ugric tongues have carried forward a non-Indo-European heritage that is every bit as European now as Latin or German. In the grand mosaic of European culture, they are the vibrant threads of a different color – weaving stories of ancient taiga hunters and steppe riders into the fabric of modern nations.

In sum, Estonia, Finland, and Hungary’s languages remain beautiful oddities in the European landscape, shaped by Finno-Ugric and Uralic roots that diverged from the Indo-European pathway eons ago. Their journey from Siberian prehistory to 21st-century EU nations is as epic as any saga – a tale of separation and convergence, of linguistic solitude and cultural kinship. And as long as children continue to learn Estonian, Finnish, and Hungarian as their mother tongue, the legacy of those ancient Uralic wanderers will live on, distinct and defiant, in the heart of Europe.

.png)

.png)

.png)