When Sweden Ruled the North

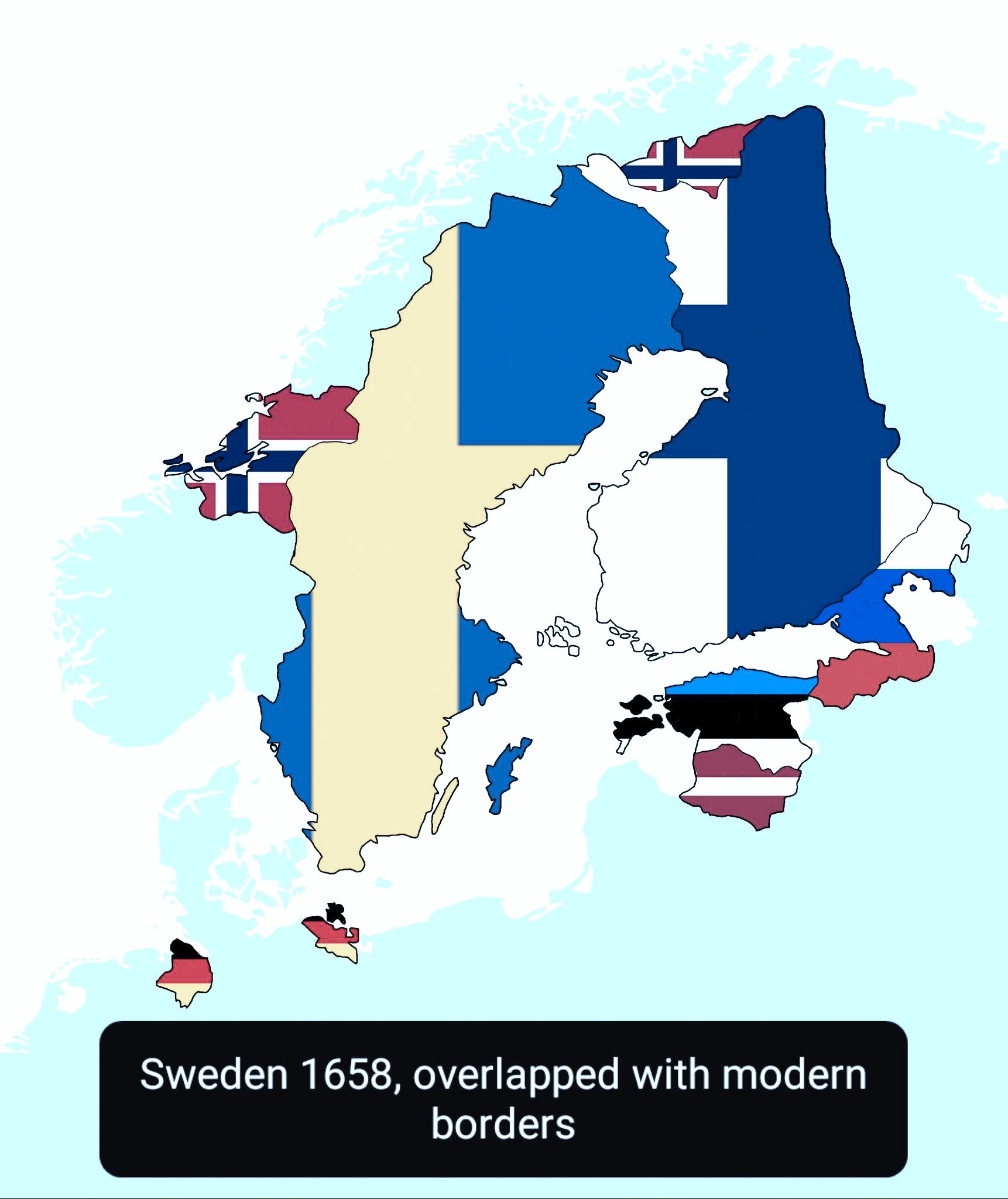

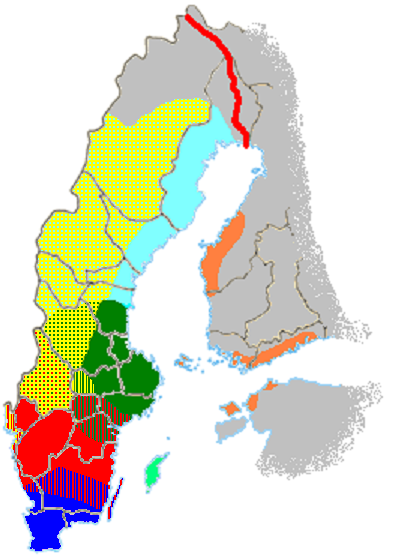

In the mid-17th century, the Swedish Empire reached an zenith that made it one of Europe’s great powers. The year 1658 marked the high point: after a string of wars and treaties, Sweden’s dominion spanned not only present-day Sweden and Finland, but also large parts of modern Estonia, Latvia, and chunks of what are now Lithuania, Denmark, Germany, Poland, and Russia.

At its greatest extent following the Treaty of Roskilde in 1658, Sweden was the third-largest European realm by land area (only the Russian and Spanish empires were larger). This vast territorial sway was hard-won through decades of conflict and diplomacy – and it left a complex legacy. In some regions, Swedish rule is remembered as a “golden age,” a time of enlightened governance and cultural flourishing, while others recall the heavy cost of empire in war and taxes. Let's explore the rise of the Swedish Empire, its cultural imprint on the Baltics and Nordic lands, the enduring traces of Swedish law and language, and the darker side of Swedish rule from the 17th century.

Expansion of a Baltic Empire (1611–1721)

Sweden’s road to empire was paved by nearly continuous warfare in the 17th century. Between 1611 and 1721 – a period Swedes call the Stormaktstiden or “Great Power Era” – the kingdom expanded aggressively around the Baltic Sea. Under King Gustavus II Adolphus (reigned 1611–1632), Sweden emerged from bitter wars with its neighbors ascendant. A peace with Denmark in 1613 ended the Kalmar War, and then Sweden turned east: the Treaty of Stolbovo in 1617 concluded a war with Russia and awarded Sweden the provinces of Kexholm (Karelia) and Ingria, cutting off Russia’s access to the Baltic coast. Next, Gustavus Adolphus campaigned against the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, capturing the rich Baltic port of Riga in 1621. By the Truce of Altmark in 1629, Poland-Lithuania ceded Livonia – roughly today’s northern Latvia and southern Estonia – to Swedish control. With that, Sweden controlled all of present-day Estonia, including the islands of Saaremaa (Ösel) and Hiiumaa gained from Denmark.

The Swedish king’s ambitions then pulled him into the Thirty Years’ War (1618–1648) on the continent. Swedish armies, well-drilled and led by Gustavus Adolphus’s innovative tactics, landed in Germany in 1630 to champion the Protestant cause. They won famous victories (like Breitenfeld in 1631) and, despite Gustavus’s death in battle in 1632, Sweden emerged from the Peace of Westphalia (1648) with new prestige and territory. As war reparations, Sweden gained West Pomerania (including the city of Stettin and the island of Rügen) and the bishoprics of Bremen and Verden in northern Germany. These far-flung acquisitions gave Sweden a foothold in the Holy Roman Empire and control of key Baltic ports. By the late 1640s, Sweden effectively ringed the Baltic Sea – earning it the moniker “dominium maris baltici,” ruler of the Baltic.

Sweden’s rivalry with Denmark-Norway, its longtime Scandinavian foe, also climaxed in this era. In 1645, the Treaty of Brömsebro forced Denmark to yield the isles of Gotland and Ösel, as well as Jämtland and Halland. A decade later, King Charles X Gustav launched a daring winter campaign, marching his army across the frozen sea to besiege Copenhagen. The resulting Treaty of Roskilde in 1658 was Sweden’s most triumphant moment: Denmark ceded the vast provinces of Skåne, Blekinge, and Bohuslän (permanently joining these to Sweden), as well as Trondheim in Norway and the island of Bornholm (though the last two were later returned). With Roskilde, the Swedish Empire reached its territorial apex. As one historian noted, after the treaties of Westphalia (1648) and Roskilde (1658), Sweden commanded the largest realm in Europe after Russia and Spain.

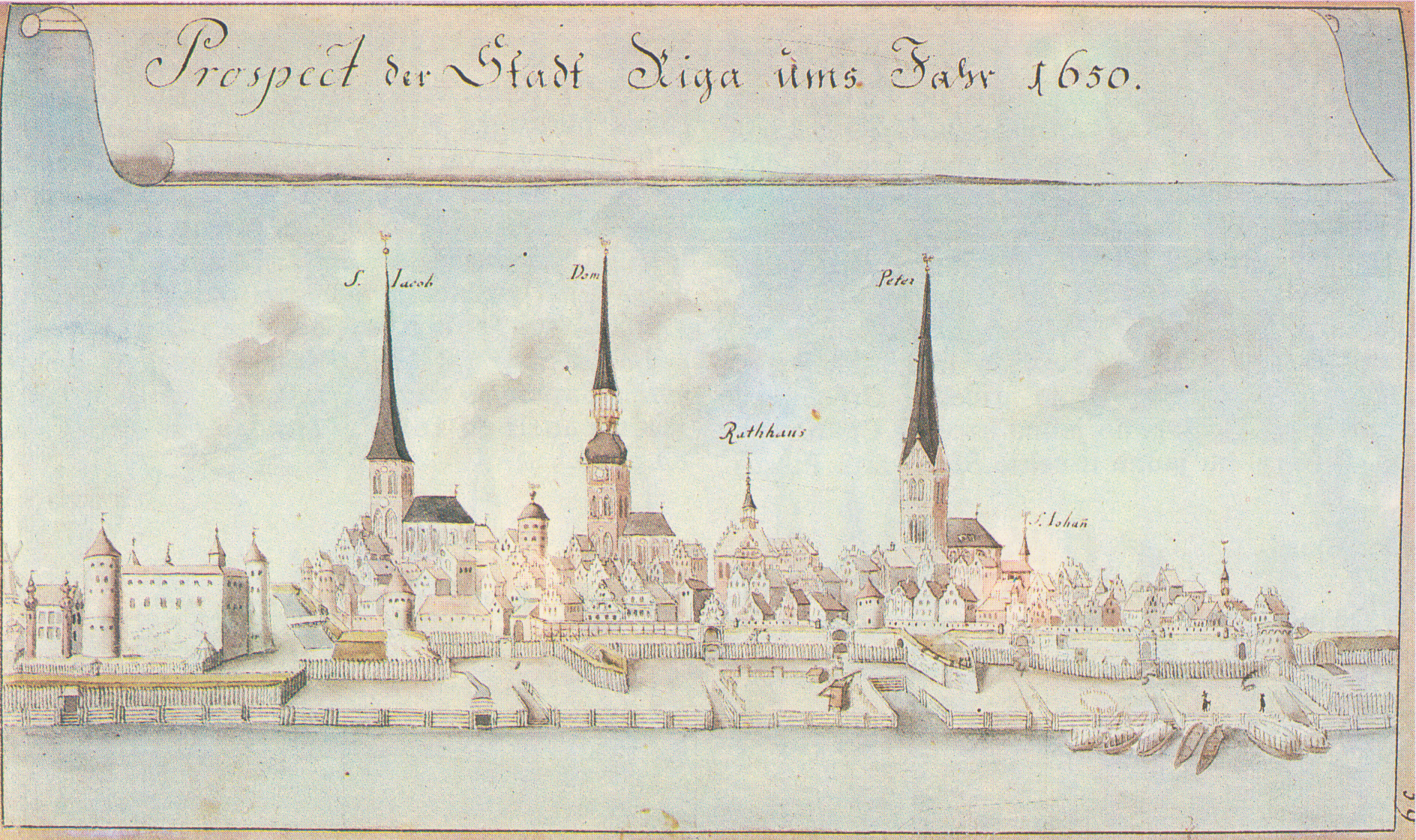

This dizzying expansion was not to last forever. In the coming decades, Sweden’s supremacy would be challenged by coalitions of neighbors. But in 1658, the empire ruled the North. Its realms included Sweden proper and Finland (then an integral part of the kingdom), Ingria and Karelia in the east (now in Russia), Estonia and Livonia (in today’s Estonia and Latvia), parts of present-day Latvia and Lithuania, the rich city of Riga (which “remained the largest city of the Swedish Empire” at the time), several North German territories on the North Sea and Baltic coasts, and southern Denmark (the Scania region). For a time, Sweden even had footholds beyond Europe – a colony in Delaware (“New Sweden”) and a Caribbean island – though these were short-lived. The empire’s vast reach around the Baltic earned Sweden a proud place among Europe’s great powers.

Cultural and Educational Influence Across the Provinces

Swedish rule not only rearranged borders – it also brought significant cultural and administrative changes to the regions under its control. Determined to govern effectively (and spread Protestant Lutheran faith), the Swedish Crown introduced its laws, education system, and church institutions throughout its new provinces. In doing so, it seeded universities, schools, and a legacy of learning that persists to this day.

One of the crown jewels of Sweden’s enlightened policy was the founding of universities in the conquered Baltic territories. In 1632, King Gustavus Adolphus established Academia Dorpatensis in Dorpat (today Tartu, Estonia). This became the University of Tartu – the second-oldest university in the Swedish Empire after Uppsala, and the first university in Estonia. Gustavus Adolphus and his Governor-General Johan Skytte envisioned educating local youth to help administer the eastern provinces “through smart and educated people”. Tartu’s academy had faculties of philosophy, law, theology, and medicine, modeled on Uppsala’s privileges. It even boasted scholarly achievements that could rival the old universities of Europe. For instance, by the 1690s a mathematics professor at Tartu (Academia Gustaviana) was among the first in the world to lecture on Newton’s new theory of gravitation – barely a few years after Newton published it. The university also operated a printing press that kicked off the era of book printing in Estonia; around 1,300 volumes were published in Dorpat by the mid-17th century. This was a remarkable leap for a land where no books had been printed before. To this day, Estonians celebrate Gustavus Adolphus as the founder of Tartu University – a statue of the Swedish king stands in Tartu, honoring his legacy as “fundator Universitatis Dorpatensis”, the founder of the university.

Finland, too, benefited from Sweden’s drive to promote higher learning. In 1640, under the auspices of Queen Christina and Governor-General Per Brahe, the Royal Academy of Åbo (Turku) was founded as the first university in Finland. It was only the third university in the Swedish realm (after Uppsala and Tartu), reflecting the priority placed on educating the empire’s far-flung subjects. The Turku academy even established the first printing press in Finland in 1642, which greatly facilitated the spread of literature and knowledge locally. These universities became vital centers of learning, producing clergymen, lawyers, doctors, and officials for the region. As a contemporary boast had it, Sweden’s Baltic provinces under its rule were “lucky” to be included in the Scandinavian cultural sphere, reaping the benefits of literacy and higher learning.

Below the university level, the Swedes introduced gymnasiums (high schools) and church-run schooling to uplift the populace. In Estonia, for example, a network of primary schools was set up to educate Lutheran pastors and schoolteachers, helping to spread basic literacy among the rural population. One notable figure was Bengt Gottfried Forselius, the son of a Swedish pastor, who opened a teachers’ college near Dorpat in 1684 to train local schoolmasters.

This was an innovative approach for its time – a early attempt at broad public education. The Lutheran Church, being the state church in all Swedish lands, also played a role in educating the common folk. Clergy were tasked with teaching people to read the catechism; Sweden was one of the first European states to aim for universal literacy (primarily so that everyone could read the Bible). Indeed, by the late 17th century, the Protestant clergy in Finland were responsible for public literacy campaigns, and high levels of reading ability were noted even among Finnish peasants. This focus on literacy had lasting effects – in later centuries, observers marveled that even captured Swedish and Finnish peasants could read, an outcome of the literacy drive under Swedish rule.

Administratively, Sweden sought to govern its empire with a relatively firm but modern hand. The conquered provinces were typically overseen by governors or governor-generals appointed from Stockholm, and Swedish law and judicial institutions were introduced.

For instance, in the 1630s Gustavus Adolphus established a Court of Appeal in Tartu for the Baltic region, so that justice could be administered locally according to Swedish legal standards. Swedish law emphasized the rule of law and somewhat more rights for commoners than the earlier feudal codes. In the Estonian provinces, especially later in the 1680s under Charles XI, the authorities took steps to curb the excesses of the German-speaking nobility over Estonian peasants. Reforms prohibited nobles from arbitrarily beating or evicting peasants, banned the sale of peasants without land, and even allowed peasants on crown lands to sue their landlords or appeal directly to the King. Although serfdom was not fully abolished in Estonia during Swedish times, the status of Estonian peasants under the Crown’s protection became “much better than the status of peasants on private lands” dominated by nobles. King Charles XI even announced an intention to abolish serfdom on royal estates, considering serfdom an anomaly in these Baltic provinces. This kind of progressive thinking earned Swedish rule a later reputation for relative justice.

Religion was another cultural aspect of Swedish influence. The Swedes were staunch Lutherans, and they propagated the Lutheran church in all their territories. In previously Catholic or Orthodox areas, Protestantism took root under Sweden’s auspices. The Bible was translated into local languages with official support – for example, the first complete Bible in Finnish was published in 1642 (translated by Mikael Agricola’s successors), and in Estonia the Lutheran clergy published Estonian-language scripture and hymnals. By promoting vernacular Bibles and church services, Swedish rule indirectly strengthened local languages and literacy. To this day, Estonia, Latvia, and Finland remain predominantly Lutheran in heritage – a direct result of the Swedish Reformation era policies.

“Good Old Swedish Times”: A Baltic Golden Age?

Ask an Estonian about the vana hea Rootsi aeg – “the good old Swedish era” – and you might be surprised by the rosy tint given to 17th-century history. In Estonian folklore and folk memory, the period of Swedish rule (1561–1710 in Estonia) is often idealized as a golden age. This phrase, vana hea Rootsi aeg, speaks to a legacy of benevolent governance and stability that people later contrasted with the cruelties of subsequent rulers. But was it really a golden age, and for whom?

There is some truth behind the nostalgia. Especially in Estonia and Livonia, the later decades of Swedish rule saw reforms that improved the lot of the lower classes. Swedish authorities curbed the unchecked power of the Baltic German nobility and introduced elements of fairness in law, as noted above. For the Estonian and Latvian peasantry, who had endured harsh serfdom under previous rulers, the Swedes’ comparatively lenient policies and respect for law stood out. Historians have found evidence that the Estonian-speaking populace came to appreciate Swedish rule for its relative justice – so much so that later, under Russian rule, some peasants would wistfully express the wish “to return to Swedish times”. Folklore remembered that under the Swedish king’s protection, farmers could not be arbitrarily flogged, and courts would uphold a peasant’s rights. Such memories were burnished by contrast: when Russia took over Estonia and Latvia in the early 18th century, serfdom was fully enforced again by the Tsar, and conditions for peasants actually worsened. Thus, the legend of a “golden” Swedish age grew in the telling.

Swedish rule also coincided with the flowering of education and local culture, which people later looked back on with pride. In Estonia, the University of Tartu produced the first scholarly works on Estonian language and folklore (Prof. Friedrich Menius began studying Estonian folklore scientifically in the 17th century). In Finland, the 17th century saw the first generation of native-born scholars and officials educated at Turku’s academy. The Finnish upper classes, many of whom were of Swedish descent or Swedish-speaking, took part in the wider Swedish imperial project. Notably, Finns served prominently in the Swedish army – the feared Finnish light cavalry nicknamed “Hakkapeliitta” rode with Gustavus Adolphus in the Thirty Years’ War. Some Finnish historians even consider the Great Power era as a shared achievement of both Swedes and Finns, since the empire drew on the manpower and resources of Finland. As historian Peter Englund remarked, Sweden’s rise as a superpower “would have been impossible for a poor nation without the resources of the eastern part of the realm” (i.e. Finland). This era, he notes, is a common heritage – the glory days of the Swedish Empire belong to Finland’s history as much as Sweden’s. It’s an interesting perspective: that Finland, though often just a “province” in Swedish eyes, was an essential pillar of the empire’s golden age.

Local people in the empire’s Baltic domains found various ways to prosper under Swedish rule. Commerce flowed freely in the Baltic Sea under Sweden’s naval dominance. Riga, which was the largest city in the empire, enjoyed considerable autonomy and continued to grow as a trading hub under the Swedish crown.

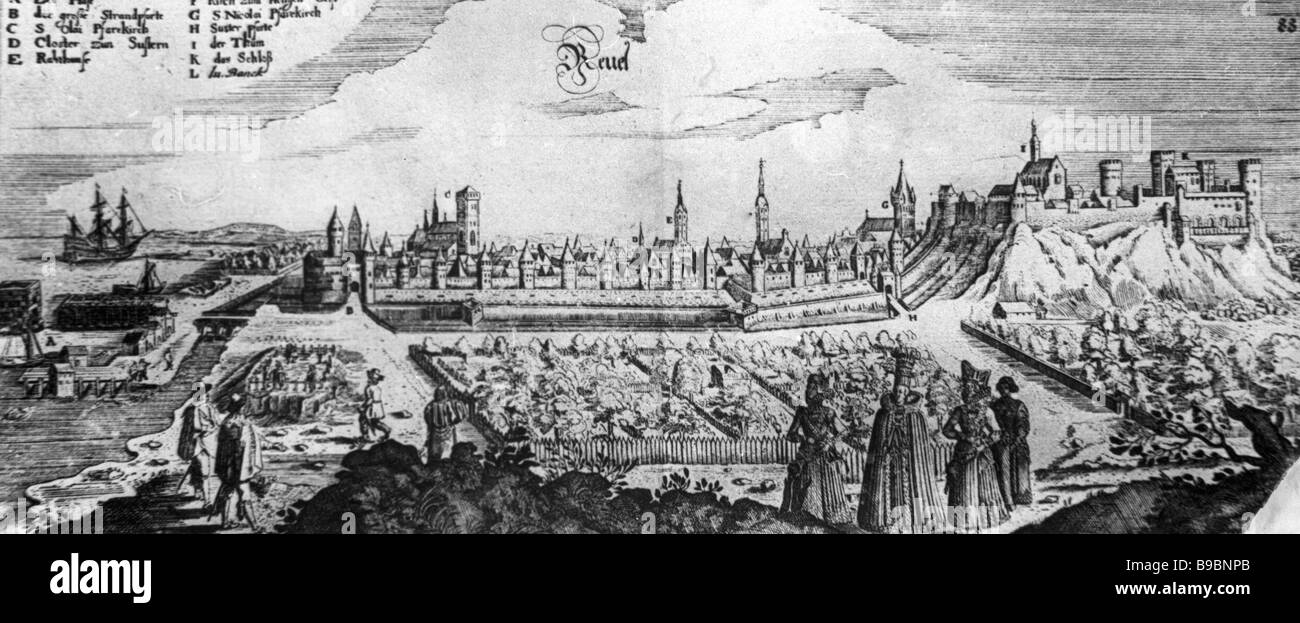

The city retained its German merchant guilds and self-government, suggesting that Sweden often ruled pragmatically, allowing traditional liberties in return for loyalty (and taxes). Likewise, the old Hanseatic town of Tallinn (Reval) in Estonia was allowed to keep its German town council and Magdeburg rights, even as it acknowledged the Swedish king as sovereign.

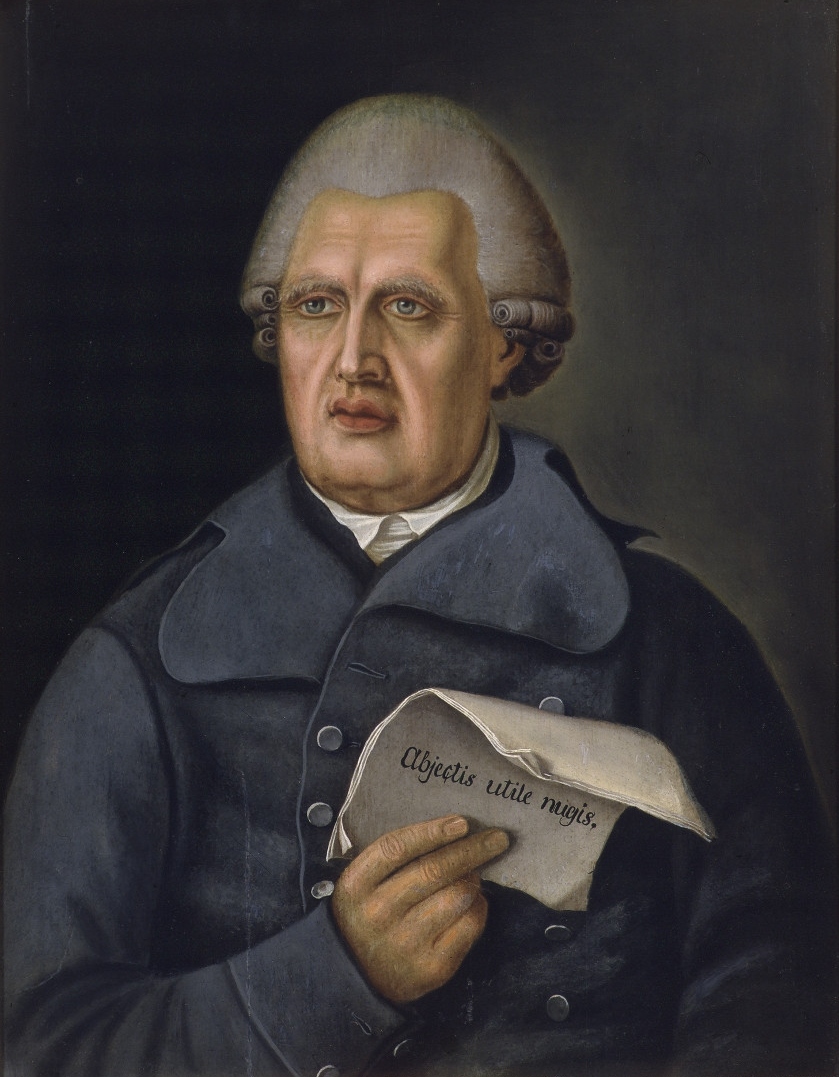

Such continuity helped cities thrive. Culturally, the mix of Swedish, Finnish, German, and Baltic influences in these areas created a unique intellectual climate. By the end of the 17th century, educated Estonians and Finns were emerging who would lay groundwork for later national awakenings (for example, Finns like Henrik Gabriel Porthan in the 18th century drew on the legacy of Turku Academy, and Estonians like Anton thor Helle who completed the first Estonian Bible in 1739 built on linguistic work begun under Swedish patronage).

To be clear, not everyone experienced a golden age during Sweden’s empire – there were famines, wars, and social hierarchies that left many commoners struggling. Yet, the reason “good old Swedish times” lives on as a saying is because relative to what came before and after, the 1600s brought notable improvements. An Estonian university rector in 2023 summed it up: “Our folklore remembers the good old Swedish times as a golden era”, pointing to the enduring idea that under the Swedish kings, justice and knowledge had a heyday. He even related a charming local legend: in Tartu, there are a hundred venerable oak trees said to have been planted by Sweden’s King Charles XII himself – “who, so the legend implies, probably had a spade on his hip instead of a sword”. Such anecdotes, however fanciful, underscore the positive light in which Swedish rule is remembered in parts of the Baltics.

Enduring Legacy: Swedish Footprints in Law and Language

Though the Swedish Empire eventually receded, its imprint on the regions it once governed remains visible today. In particular, the legacy survives in legal systems, languages, and cultural habits across the Nordic and Baltic countries – a testament to the deep influence of a century of Swedish hegemony.

One major legacy is legal. Swedish law and administrative practice were implanted in Finland and the Baltics during the 1600s, and in some cases continued to be used long after Swedish rule ended. In Finland, which was part of Sweden for nearly 600 years, the entire legal code and social structure was Swedish-derived. Feudal serfdom never took hold in Finland under Swedish rule – Finnish peasants were freeholders or tenant farmers, not serfs, and this personal freedom persisted into modern times. The Swedish legal tradition emphasized contracts, local representation (through things like village law courts and provincial diets), and the protection of certain peasant rights. When Russia took Finland in 1809, the new Grand Duchy actually retained the old Swedish laws as its governing laws – a deliberate choice by Tsar Alexander I to reassure the Finns. As a result, aspects of Finnish law (and even some official terminology) in the 19th century were essentially 18th-century Swedish law. Today’s Finnish civil law has evolved, but the structures – an independent judiciary, strong rule-of-law ethos, and even the appeal court in Turku (established 1630s) – have roots in the Swedish period.

In Estonia and Latvia, Russian rule in the 18th–19th centuries wiped away some Swedish institutions, but notably the Baltic civil law preserved many German/Swedish legal customs until the 1860s. Even the modern Estonian and Latvian legal codes, being continental European in style, owe something to that blend of Swedish and German law from the colonial period.

Language is another arena of Swedish influence. In Finland, Swedish remained an official language and the language of the educated elite well into the 19th century. Even though only about one-eighth of Finns had Swedish as their mother tongue by the 1800s, Swedish was dominant in administration and higher education until Finnish nationalism rose. To this day, Finland is officially bilingual; about 5% of Finns (especially along the coast) speak Swedish natively, and nearly everyone learns at least some Swedish in school. This is a direct legacy of the centuries as part of the Swedish realm. Finnish itself absorbed a huge number of loanwords from Swedish during the long union. Linguists estimate some 1,100 Swedish-origin words made it into the Finnish vocabulary during the Swedish era (often originally loans from Latin or German via Swedish). For example, words for government, city life, and modern institutions in Finnish often come from Swedish roots. The imprint is so deep that everyday Finnish contains traces of 17th-century Swedish in its DNA.

In Estonia and Latvia, Swedish as a language did not take root among the general population (German remained the lingua franca of the Baltic gentry, and native Estonian/Latvian was spoken by the peasants). However, Sweden did leave behind small Swedish-speaking communities. Along Estonia’s coast and islands, communities of “Coastal Swedes” (rannarootslased in Estonian) lived for centuries – descendants of Swedish fisher-farmers from the medieval era who were protected under the Swedish Crown.

Place names like Ruhnu (Runö) and Noarootsi (Nuckö) hint at this heritage. Some of these communities survived into the 20th century, and their presence is fondly remembered; Estonia even thanked Sweden in recent times “for the free Estonian Coastal Swedes” who were supported and given refuge when needed. Culturally, the Swedish period also tied these countries into the Scandinavian world. Estonians and Finns sometimes characterize themselves as “Nordic” nations in part because of the long Swedish connection. For instance, the concept of Baltoscandia – grouping the Baltics with Scandinavia – was put forward by 20th-century geographers to emphasize the common cultural space created in part by Swedish rule.

Other customs and institutions introduced by the Swedes have stood the test of time. The Lutheran Church remains the majority church in Estonia, Latvia, and Finland, as mentioned, which owes largely to the Swedish Reformation’s enforcement. In Finland, the Church’s early role in maintaining literacy and vital records endured; even today the Lutheran Church in Finland is involved in community life in a way reminiscent of its state-church function under Sweden. The idea of local self-government through parish or county councils can also be traced back to Swedish administrative reforms (Queen Christina’s 17th-century regulations set up local parish schools and parish councils, for example). Additionally, Sweden’s tradition of maintaining land registers, efficient tax collection, and a professional civil service influenced how these countries developed their bureaucracies. One quirky legacy: the Finnish and Estonian national colors (blue-black-white for Estonia, blue-white for Finland) arguably connect back to university student movements in the 19th century, which in turn harked to the universities founded by the Swedes (the University of Tartu’s student societies, for instance, were crucial in fostering Estonian national consciousness). While not as obvious a link, it’s a chain of influence starting in the 1600s.

Perhaps the most positive legacy is intangible: the notion of being part of a “Nordic” or Western tradition. By pulling Finland and the Baltics into its empire, Sweden oriented them toward Western Europe rather than leaving them in an Eastern sphere. Finland was integrated into the Western European cultural sphere – as one Finnish site notes, it became part of the Western market economy, constitutional governance, and legalistic principles under Sweden. Estonia, too, saw itself as different from Russia and more aligned with Nordic values, an identity thread that carries through to today’s Baltic-Nordic cooperation. These self-conceptions owe a debt to the Swedish age.

The Other Side of Empire: War and Hardship under Swedish Rule

Golden age or not, the Swedish Empire’s dominion was not an unalloyed blessing. Many in the subject territories paid a steep price for Sweden’s imperial ambitions. The 17th century was an era of almost endless war, and the Baltic provinces and Finland were often treated as resources for the Swedish war machine. Military conscription and exploitation were a constant under Swedish rule. A significant portion of Sweden’s army consisted of Finnish and Estonian soldiers – so much so that in the Thirty Years’ War and other conflicts, entire regiments of Finns (the “Hakkapeliitta” cavalry, for example) fought and died far from home. The toll on these regions was heavy. Contemporary accounts and later research note that “a significant part of the peasants had to serve in the army and navy, and many of them died in service” during Sweden’s great power wars. Almost every generation saw a new war – against Poland, against Denmark, against Russia, against whomever the crown’s policy targeted – and the young men of Finland, Estonia, Livonia, and Ingria were continually levied to fill the ranks. The Great Northern War (1700–1721), which finally broke Sweden’s power, was especially devastating: as Russian forces invaded in 1708–1710, they laid waste to Finland and the Baltics. In Finland, the period of Russian occupation (1714–1721) is remembered as the “Great Wrath,” when thousands of Finns were killed or deported as slaves and entire areas were ravaged. The fact that Swedes had earlier barred serfdom and slavery didn’t protect Finns from being sold in Russian markets when the tide turned. In short, the common folk caught in the middle paid dearly, whether under Swedish rule or during its collapse.

Taxation was another burden. Empire-building required funds, and much of that was extracted from the provinces. In Finland, roughly half of all taxes collected were sent to Stockholm to fund the central government and the military. This was a considerable drain on a poor land. Peasants often complained of high taxes and requisitions – not only coin, but also grain, livestock, and labor could be demanded to support Sweden’s armies. In Estonia and Livonia, the Swedish authorities initially left tax collection to the German nobility (who were the landlords), but later the Crown’s “reduction” of noble estates in the 1680s was aimed at increasing state revenue. Charles XI’s great Reduction stripped land from the aristocracy to bolster royal finances. While this curtailed noble excess, it also meant peasants on former church or noble lands became crown tenants and owed obligations directly to Stockholm. One can imagine that for a Latvian peasant, whether he owed grain to a German baron or to the Swedish king, the load was still heavy.

Culturally, one could argue there was a degree of suppression or neglect of local languages in favor of the rulers’ tongues. In Finnish territories, Swedish was the sole official language of government, and Finnish speakers faced challenges in dealing with authorities because of that linguistic barrier. Many Swedish governors-general didn’t bother to learn Finnish. Some Swedes of the time viewed Finns as a conquered people, “primitive” with an “inferior” language, and not equal to Swedes. This attitude hindered the inclusion of Finns in higher offices. In Livonia and Estonia, Swedish officials generally communicated in German (the language of the local elite) or in Swedish; Estonian and Latvian languages had no official status. While the Swedes did encourage publishing the Bible in those tongues for church use, they didn’t elevate Estonian or Latvian in administration. Near the end of the Swedish era, a professor in Turku, Israel Nesselius, even proposed a plan to “Swedify” Finland completely – by teaching all Finns Swedish and settling more Swedes in Finland, hoping to essentially erase the Finnish language over time. This scheme did not come to pass, but it illustrates the mindset of some Swedish elites that minority languages were to be assimilated. In that sense, one could criticize Swedish rule for what today might be called a colonial language policy, even if it was milder than later Russification policies would be.

The human cost of war under Sweden’s expansive campaigns was not limited to Swedes and their subjects – it was also borne by their enemies, often civilians. A stark example is the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth’s experience during the mid-17th century “Swedish Deluge.” When Sweden invaded Poland and Lithuania in 1655–1660, it led to one of the greatest catastrophes in Polish history. Swedish armies and their allies plundered the land mercilessly. Cities like Warsaw and Kraków were sacked; Warsaw’s population fell from 20,000 to only 2,000 after the Swedish occupation and a concurrent plague outbreak. The war and its related conflicts caused Poland-Lithuania’s population to plummet by an estimated 30–40%. Millions perished from violence, famine, and disease in those years. Polish historians rank the Deluge as a national trauma second only to perhaps World War II in terms of demographic and cultural devastation. This illustrates that Sweden’s imperial glory had a dark shadow – what was a triumph for Stockholm often meant tragedy elsewhere. Even in Denmark, one can imagine the bitterness of ceding ancestral provinces like Skåne to Sweden; efforts to “Swedify” Scania in the late 1600s met resistance and rebellion as locals chafed under new masters.

Finally, while Sweden prided itself on being more “enlightened” than its rivals, one should note that the class system of the time still left many underprivileged. The “golden age” glow tends to overlook that peasants in Estonian and Latvian lands remained enserfed to local lords (only slightly mitigated by Swedish reforms) and had no political rights. In Finland and Sweden proper, only the small farmer class and bourgeoisie had representation in the Riksdag (Swedish parliament), alongside nobles and clergy. Poor landless folks or the urban poor had no say. Thus, many ordinary people might not have felt empowered under the great power, even if they did enjoy peace or better laws now and then. And when nature struck – such as the Great Famine of 1695–97, which hit Finland and Estonia hard – Swedish authorities struggled to provide relief. In Finland, the famine of those years (caused by cold weather and crop failures) led to the starvation of an estimated quarter to a third of the population.

.jpg)

Some have criticized the Swedish government for not doing enough, as troops were prioritized for provisions over peasants. Such suffering tempered the memories of the 17th century for those who lived through it.

A Legacy Written in Oak and Iron

The story of the Swedish Empire at its height is one of contrasts. It was a time when the North was, for a brief period, ruled from Stockholm – when Sweden’s kings could claim dominion from the German ports of Wismar and Bremen to the far side of the Gulf of Finland. In the lands we now call Estonia, Latvia, Finland and beyond, that era left marks still visible centuries later. Universities, legal codes, and even living languages carry forward the legacy of the “Swedish century.” In Estonia, the collective memory of vana hea Rootsi aeg speaks to that legacy of fair rule and intellectual bloom, even as academic debates remind us that not everyone experienced those times as “good.” In Finland, seven centuries in the Swedish realm forged a nation that today speaks two tongues and looks westward for its affinities. And across the Baltic, one can find Swedish place names, ruined fortresses with three crowns insignia, and cultural threads connecting back to the days of empire.

Yet, empire by its nature is double-edged. Swedish rule brought schools and scripture, but also swords and conscription. The same King Karl XII who legendarily planted oak trees in Tartu also led countless Finnish and Estonian lads to die on the battlefields of Poltava. The same laws that protected a peasant from a cruel baron also bound him to give up grain and sons for the Crown. History must be honest about these contradictions. The Swedish Empire’s footprint in Northern and Eastern Europe was significant and in many ways beneficial – laying foundations for education and governance – but it was not gentle or bloodless.

For the descendants of Nordic and Baltic immigrants in North America, this legacy is a proud part of our heritage: the idea that from Tallinn to Turku, there was a time of common endeavor under the Swedish flag, a time that shaped the destinies of those regions. It is the reason universities like Tartu celebrate Gustavus Adolphus Day each year, or why Finland’s legal traditions align with Sweden’s, or why an Estonian might still plant an oak tree and whimsically think of Karl XII. The Swedish Empire may have been short-lived on the scale of history (barely a century as a great power), but its cultural and political imprint far outlasted its military might. In the end, that imprint – the laws, the languages, the schools, and yes, even the legends – is the true legacy of Sweden’s “golden age” across the Baltic. It lives on in the everyday fabric of Northern Europe, a testament to a time when the North was one under a Swedish suzerainty that sought both to conquer and to enlighten.

.png)

.png)

.png)